The next level

Successful contenders in today’s chess matches are those who know as much as possible about the ways their rivals play the game. The reason is that the contenders know each other and the preferences of their opponents: their favorite openings, strategic moves, variants in the middle and end game. Databases and computer programs have created transparent chess players.

Now 30 years old, he’s held the top spot in the world ranking since 2011 – even though in October, after 125 consecutive wins, he lost two games for the first time© Dean Mouhtaropoulos/Getty

That’s why in today’s top-caliber chess competitions being prepared is the name of the game. Knowing in advance how to best respond to the opponent’s maneuvers leads to success. On the other hand, players must continue to play in variable ways and surprise their opponents, who are equally prepared, with ever new variants and strategies. Up until the mid-1980s, the situation was completely different: chess was an analog game. Grandmasters like Anatoly Karpov used to dominate this discipline strictly because of their experienced courses of action, fast thinking and strategic skills on the chessboard.

Until Garri Kasparov came. Or the computers. Or both. Because when Kasparov snatched the world champion’s title from his rival Karpov in 1985, he also achieved this with the help of the new technologies. Kasparov is deemed to be one of the first world-class players to have carefully calculated his games by means of computer programs and to have had his computers play and gauge diverse variants. Assisted by the new technologies, Kasparov acquired leading-edge knowledge that rivals like Karpov weren’t able to compensate for in spite of all their imagination and playing strength.

Kasparov’s title win rang in a new era in chess that was subsequently shaped by databases and computer programs. ChessBase is the worldwide leader in this sector. The Hamburg-based company built a huge database on which by now more than eight million previously played chess games can be accessed. In addition, the providers from Hamburg are selling computer programs enabling players to analyze chess games and play countless variants in a matter of seconds. The most prominent client is the reigning world champion Magnus Carlsen. The 30-year-old Norwegian ascended to the world champion’s throne in 2013 – naturally also with the help of modern technologies. Like his rivals, Carlsen is supported by a team that assists him in his work with databases and computers. On his own, the “Mozart of chess” would never be able to calculate his way through the chaos of variants, positions, openings and strategies.

4 hours of learning

This is how long it took the artificial intelligence AlphaZero to defeat Stockfish, the leading database-supported chess program to date. In 2017, AlphaZero won 28 of 100 games, 72 ended in a draw and none was won by Stockfish. A year later, AlphaZero’s tally after the 1,000-game duel involving changes in time for consideration and more data sources for Stockfish reflected 155 wins, 839 draws and 6 defeats. AlphaZero is regarded as a true game changer in the world of chess and stuns audiences with unconventional strategies. Even World Champion Magnus Carlsen adapts the AI to his game without any reservations. “In essence I’ve become a very different player in terms of style than I was a bit earlier and it’s been a great ride,” he says. However, AlphaZero’s abilities aren’t limited to chess. AlphaZero decided the duel against AlphaGo, the computer that in 2016 defeated the world’s best Go player for the first time, 60–40 in its favor – after just eight hours of learning.

AI kickers

The first thing a professional player from TSG Hoffenheim does when he wakes up in the morning is listen to his inner voice: “Did I sleep well? Am I on top of the world or rather tense? Am I in good health?” Then the player of the Bundesliga club will start the club’s app on his smartphone and send the responses to his employer at the training center.

“In the last ten years, a lot has happened in professional soccer in the wake of digitalization. The development of technical opportunities has fundamentally intervened with the processes of this game and massively changed it,” says Rafael Hoffner, who has been leading the IT & Infrastructure department at TSG Hoffenheim since 2009.

While coaches used to be “soloists,” a whole team is now sitting on the bench of every Bundesliga club. All of them are connected to each other via an internet port and a network. Tracking systems provide running and dueling information about the players, and match analysts distributed across the stadium additionally deliver their impressions and data. The strategy is: stay as variable as possible, keep surprising your opponent. “Match plans are subject to constant change today. A team wants to remain as unpredictable as possible for its rivals,” says Hoffner.

By now, most top-flight soccer clubs have largely followed suit in terms of technology, although the Hoffenheim team still benefits from its early strategic interest in innovations. “We’ve been gathering data about our players for more than ten years, so we’re familiar with their strengths and know in detail what we need to work on,” says Hoffner. As a result, a player may have to spend more hours working with the sports psychologists while another one will intensify his work with the footbonaut, a ball machine for enhancing a player’s passing and shooting techniques.

In addition to the footbonaut, Helix, a virtual room, can be used by the players to hone their cognitive skills. Video footage displayed across the 180-degree projection area of the screens puts the players into a variety of playing situations, requiring them to respond accordingly. The training is centered on concentration, perception and peripheral vision. At Hoffenheim, they know a lot about their players. Will the wealth of data soon culminate in a predictable strategy? “No,” says Hoffner, “humans will always remain unpredictable to some extent. And that’s good!”

1 million data points

A small tracking system worn directly on the body is all that’s needed to capture a soccer player’s movements. Obviously, it shouldn’t restrict the players’ ability to move. That’s why companies like GPS-Sports and VX Sport install the technology in a sports bra. It sits on the torso without impeding the athletes during their training sessions. Via a GPS signal, the gadget creates a movement profile, records speeds, and analyzes efficiency on the pitch. In a 90-minute training session a million data points are generated. Via radio communications, the data are sent to computers on the edge of the pitch or can be read within a few seconds by means of a docking station.

All chips on deck

When Jochen Schümann sailed to his first in a total of three Olympic gold medals in Montreal in 1976, he did it completely on his own. He was solo-sailing a Finn dinghy and used the prevailing forces of nature strictly by instinct: the wind direction and wind force, water currents and assessment of the small- and large-scale weather developments. For the first time Schümann back then proved his by now legendary intuition and talent for sailing to an international audience – and at the mere age of 22 outperformed all of his competitors.

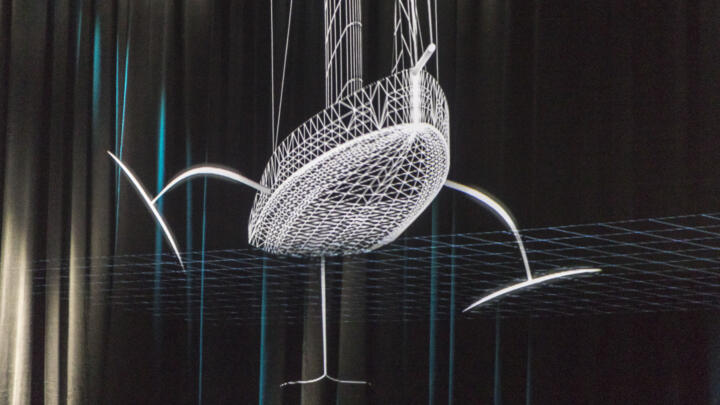

Sailing, today, only has little to do anymore with the sport back in those days. Schümann says: “In the course of time, sailing has become increasingly complex. The progress made in terms of hardware and data analysis has caused an enormous evolution of the sport and turned it into a veritable science.” Lighter and lighter materials for the hull, sails, ropes and masts have been making the boats faster and faster. Most recently, foil technology causing the boats to “fly” across water on wing-like hydrofoils has led to an explosion of speed that was hardly considered to be achievable. These gliders can reach speeds above 90 km/h (56 mph).

Arguably, the most decisive development to have immensely influenced strategy and tactics, as well as the design of the sail boats, is data collection and use: a process that in recent years has been massively accelerated by software companies like Oracle and SAP having entered the sailing arena. Depending on the boat class, dozens and sometimes a thousand and more sensors and GPS trackers capture every movement in water and on board, collecting vast amounts of data in the process. Weather and ocean current data, and even the salt content of the water, are digitally dissected and analyzed. As much as 16 gigabytes per day may be generated in this way.

While in the smaller Olympic boat classes external technical support during a competition is prohibited, the sailors of large boats in multi-million dollar regattas like the America’s Cup and the Volvo Ocean Race take advantage of the enormous new opportunities also during the race: rudder angle and position, tension of sail ropes, angle of list, etc., etc., etc.: All this information is sent “live” to the computer at the command post and affects the helmsman’s decisions. The sailors of smaller boats benefit from the technology primarily after a competition – while preparing for the next race. In interaction with data about currents and wind conditions that sailors once used to have to tediously record by hand, athletes today benefit from an overall analysis within seconds after crossing the finish line that makes completely new tactical and strategic considerations possible between the individual races.

Another advantage: By means of software programs the positions of the sailors can be digitally transmitted. The positions of the boats in front of buoys, at the turning points and before the finish line are depicted with accuracy down to an inch. This is good for the spectators’ overview, for organizers and reporters.

The data gathered are worth a mint with respect to the design of the boats as well. “Design without data, well I’m not sure what it is,” says Mauricio Munoz, an engineer with America’s Cup experience under his belt, and adds that “this is as much a design race as a sailing race.” Jochen Schümann won’t go as far as that. “The data analysts,” he says, “have an enormously important job today. Based on their information, sailors can build their strategies against the competition.” However, in his view, the athlete’s intuition is still indispensable even today: “At the end of the day, it’s like in any highly advanced performance sport: the existing data volume provides a basis. But on the water, at the crucial moment, ingenious athletes have to make the decisions. And no computer can do that for them.”

Nearly 100 km/h (62 mph)

This is the speed at which the new AC75 monohulls of the America’s Cup glide across water. The battle for the world’s oldest sports trophy is regarded as the multi-million-dollar top category in sailing. The key to success is to optimally merge the variables from the areas of hardware (sails, foils), nature (wind, waves, current) and opponents in a suitable strategy.

Innovation from the high-speed lab

2020 DTM finale at the Hockenheimring. Even before the current champion is determined in the last races of the top touring car class this season, the future of the racing series begins. A demo car of the DTM Electric does some laps in the Motodrom section of the race track in Southern Germany. With nearly 1,200 horsepower, the electric car runs on the performance level of Formula One.

In terms of vehicle dynamics, it reaches new dimensions, because the four battery-electric motors from Schaeffler can wheel-selectively be controlled for perfect traction in all conceivable track conditions, a technology referred to as torque vectoring. Acceleration is impressive as well. The sprint from zero to 100 km/h (62 mph) takes 2.4 seconds. That’s 0.4 seconds less than the current DTM car needs: just a blink of the eye but one that means ages on a race track. In 2021, further demo runs of the DTM Electric are to follow. The first competitions are planned for 2023. The prototype was developed in close collaboration between the DTM’s umbrella organization ITR and Schaeffler, the DTM’s future series and innovation partner. In addition to the powertrain and other components, the renowned automotive and industrial supplier contributes to the prototype the Space Drive steer-by-wire technology that has already been tested in motorsport. Together, the partners are showing what the future of motor racing may look like: green, highly performant and electric.

The partnership with the DTM is a perfect fit for Schaeffler. As a pioneer, we want to lead the way, challenge the status quo – and thus make the difference

Matthias Zink, CEO Automotive Technologies at Schaeffler

“We look forward to this partnership,” says Matthias Zink, CEO Automotive Technologies at Schaeffler. “Our innovative electric powertrain technologies have been producing victories in Formula E since 2014 and are now used in production vehicles as well. This collaboration is proof of a pioneering spirit and innovative prowess and, as a technology partner, underscores our aspiration of shaping progress that moves the world.”

The HYRAZE League, the world’s first automotive racing series to use as its energy source hydrogen produced by means of environmentally friendly technology, is planned to start in 2023 as well. Schaeffler is involved in this project, too. The races will be held with 800-hp hydrogen cars. The energy for the zero-emissions powertrain is supplied by “green” hydrogen converted in the two fuel cells of the race cars into electricity for the four electric motors. In addition, energy recuperated during braking events is stored in compact high-performance battery cells.

Other areas of the HYRAZE car have plenty of sustainable innovation on board as well. The body parts, for instance, are produced from a natural fiber composite material. Another unique feature in international motor racing will be the braking system of the all-wheel-drive vehicles: None of the brake dust generated will be released to the environment in an uncontrolled manner but trapped in the vehicle and subsequently disposed of with no environmental impact. Moreover, special tires developed from renewable raw materials will minimize tire wear particles. Combined with a strictly limited number of tires, this will considerably reduce fine dust pollution.

Another example of innovation is the combination of e-sports and real-world motorsport in the HYRAZE League. The teams will have two drivers for each car: one for the real-world classification races and one who will compete in the e-sports events that are also part of the championship. The results of both races will be counted equally in the championship classification so that in the end one team will be the overall winner in both disciplines: an absolute first in motorsport.