Be brave!

I’ve interviewed more than 150 captains over the years. Much of what they weathered out in the eye of a storm – with composure, courage, conviction and confident energy – can be applied to life in general – including business life. Captains coping with heavy seas can serve as role models for business leaders that need to resolve conflicts and crises.

Sometimes it’s a matter of life and death, like in the case of Captain Emil Feith from Hamburg, who safely navigated the “Svea Pacific” bulker through a hundred-year storm. The hurricane at that time was roaring with a ferocious force that even this seasoned sailor had never experienced before. In front of the bridge, a mix of foam and waves formed a gray wall. Bangs were resounding through the ship and the steel was screaming. An officer asked the captain to go to the lounge, one deck below the bridge, where the international crew had gathered. The men, paled with fear, were staring at the inferno outside. They were wearing life vests.

All that happened in the fall of 1991. On the North Atlantic, a hurricane and an arctic low-pressure area had united into what meteorologists would call the “perfect storm.” Hollywood turned that tempest into a blockbuster movie starring George Clooney as the doomed protagonist. It was in the thick of this rough reality that the “Svea Pacific” bulker, with Captain Feith on the bridge, was torn back and forth by the breakers. My admiration of his resilience, of his tenacity and of his gift of seeing his ship and his crew through tough times keeps growing with each word that he’s telling me.

Just whistling fright away

“I wasn’t sure we were going to make it,” said the old seafarer. “To be honest, I believed less and less that we would with each passing hour.” How that feat was achieved anyway? It was done wave by wave. To prevent a panic from breaking out, Feith reached for a cassette his wife had packed for him. It was a recording of Johnny Cash singing a song about rising water: Five feet high and risin.’ The captain whistled the tune as if the ship were cruising in the Hamburg harbor on a summer day instead of navigating the hostile Northern Atlantic. When the chief engineer entered the lounge, asking – in German -- what the situation was like, Feith responded,” Doesn’t look good.” Then both men grinned as if they’d been telling a dirty joke – and bawled the crew out in English for being such sissies. The red herring worked.

“At times, a captain needs to be an actor.”

Captain Emil Feith

Now, following the coronavirus and in a global geopolitical situation that has become more critical due to the war in Ukraine, all of us are caught in a massive storm. Uncertainty can be felt everywhere and deeply affects our professional and personal lives. Our jobs, our families, our friends. Many people are asking themselves how do I navigate my ship – my business, my family – through the storm in reasonably safe ways? If there’s anyone who’s intimately familiar with that question it’s captains.

I can detect patterns in their actions. How they prepare for rough weather. How they guide their crews and navigate their ships through a tempest. I’m convinced that the calm actions of captains contain approaches that can be applied to daily life. That applies to anticipating a hurricane and taking appropriate precautions just like it does to the question of how to keep cool amidst the greatest chaos. How to project authority, strong leadership and thus confidence without acting like a dictator. How far you trust yourself and others and whether you allow your own emotions, particularly fear, to get the best of you.

Clear thinking, clear actions, clear messages

Which takes us to the subject of the “service face.” At times, a captain needs to be an actor, Captain Feith told me. In critical situations there’s no room for emotions – and it’s generally inappropriate for captains to share their emotions with others anyway. “Emotions,” the way he said it, sounded like something repulsive you wouldn’t want to have under your shoe.

Clear thinking, clear actions, clear messages, time for the “service face.” I like the concept not least because it seems to be so anachronistic today when everyone turns their inside out in social media. In turbulent times, when people are worried, excessive emotionalism exacerbates things, whereas the “service face” communicates calmness and determination. Determination to fight for the ship and crew up to the last minute. That the captain’s leadership role is not about wielding power is an important aspect in this regard. The opposite is true. Not being full of themselves is a special trait of many old captains. More “we” and less “I” because even the most seasoned shellbacks realize that they cannot safely steer a ship to the nearest port without the backing of a loyal crew. That’s why, as an exemplary leader, it’s crucial especially in turbulent times to get your team to back you unconditionally – come hell or high water.

“There’s no place in the world that makes you feel as small and insignificant as the North Atlantic in a storm.”

Many stories that captains tell are about highly dramatic events between life and death. About fierce storms, about monster waves, about problems with cargo, but to most of the mariners I talked to it was extremely important that their stories would not come across as boastful tales.

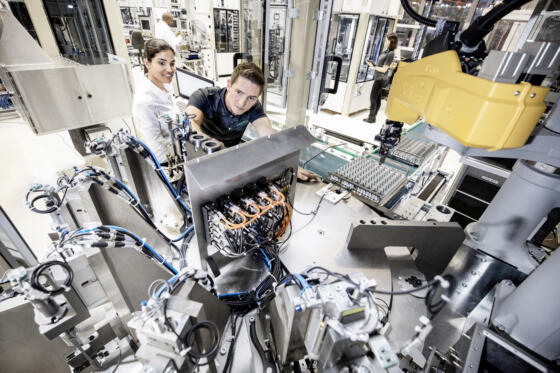

Obviously, no one weathers a storm solely with a captain’s acumen. Another matter of vital importance is the ship’s technical condition – which is why most captains I know are sticklers at sea. The ship, especially the engine, must be in good state of repair, and it’s all about details. Whether I joined them on board of a cruise ship, on a freighter or for an excursion on the Elbe River, the first thing the captains would inspect was the condition of the lifeboats. They’d check if the davits were lubricated and if the escape routes were clear. They’d complain whenever someone ignored the safety information.

Catastrophes are not monocausal

While I was traveling on a cruise ship with Captain Jürgen Schwandt, he got upset about the safety officer having long hair and wearing an untucked shirt. Another time he complained about the presence of a potted plant on an escape route. That’s a no-go! He immediately demanded to talk to the duty officer and asked him if in case of an emergency he really planned to take care of that rubber plant. The potted plant was gone shortly afterwards. There’s a simple notion behind this putative pedantry. Catastrophes typically are not monocausal events but the sum of many minor mistakes. It follows that if minor mistakes are corrected major failures are less likely. From that perspective, a minor problem already starts with a safety officer not caring about whether their shirt is tucked in.

“With a functioning crew and a strong ship, I can pull through anything. There’s no need to worry in that case,” Johannes Hritz, a trawler captain from Bremerhaven, told me. During his daily routines on the North Atlantic, he’s sometimes confronted with waves as tall as seven-story buildings. That’s no problem when all hands on deck work together and are on guard the way they should be.

“With a functioning crew and a strong ship, I can pull through anything.”

Hritz told me that that’s the reason why he likes to work with sailors he’s familiar with. He also said that he paid attention to people on board treating each other respectfully. Resilience is part of the job – as is a certain toughness. In the event of a suspected heart attack, in cases of broken bones or renal colic, he heads for a port. But in case of, say, cuts? They can always happen. “For such cases, we’ve got a stapler on board,” he says. I can imagine how that would go over with people working in any kind of onshore job.

Another thing I like about the attitude of the old captains is their active pragmatism. They’ve charted a course. They’ve got a plan. But when it’s necessary they’ll change it as needed. That makes captains true resilience pros – even though that expression hardly rings a bell with them.

I remember the story of a mariner from Hamburg who during a severe hurricane in the Bay of Biscay came to the rescue of a motor vessel from Denmark in response to a mayday signal. The ship reported engine trouble and inrush of water. “Please pick me up, sir,” the fellow captain was pleading over the radio. That, however, appeared to be near-impossible in the heavy swell. The Danish crew ultimately boarded an inflatable rescue raft that the storm quickly caused to drift away. After realizing that a line connection with the raft could not be created in any other way, Captain Peter Steffens put his ship in reverse in the crucial moment. Steering a freighter in reverse – in a hurricane? Unconventional but successful. A maneuver for which other captains no doubt criticized him, Steffens said. So what? The Danish crew was out of danger. Steffens and his crew managed to pull the shipwrecked sailors up on their ship’s side.

Reaching the next port is the top priority for all captains, as is the safety of the crew. For most captains, the thought of losing a crew member at sea is unbearable. When it does happen, it continues to trouble them even decades later.

Captain Feith, with whom this story started, was one of the mariners making it through the hundred-year storm. In spite of engine failure. In spite of an inrush of water below the water line which the pump just barely managed to keep in check. When Feith and his freighter arrived in Liverpool the angry hurricane had knocked all the paint off the ship. Bare steel was visible in many places, and the cargo – T-beams for a high-rise building project – was reduced to scrap value because its exposure to salt water would cause the construction material to corrode. Steel may be tougher than sailors but it’s not more resilient …

The most important thing, though, was that they’d survived.

On course for resilience

Ocean shipping accounts for more than 80 percent of global trade. Consequently, the resilience of the fleets is one of the crucial connecting links to prevent a disruption of strained supply chains. The UN’s 2022 Maritime Transport Report points out vulnerabilities.

- The international ocean fleet is getting on in years. The current average age of all freighters sailing the seas is almost 22 years. Putting age in relation to cargo capacity, the average drops to 11.5 years, which means that bigger ships are younger on average than smaller ones. But that’s no reason to give the all clear because many shipping companies are shying away from capital expenditures due to uncertainty regarding technological developments, frequently changing environmental requirements, increasing borrowing costs, and blurred economic prospects.

- Despite new technologies the CO2 emissions of the worldwide ocean fleet went up by 4.7 percent between 2020 and 2021, with container ships, bulk carriers and general cargo vessels accounting for the lion’s share of that. The UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) demands more capital expenditures to be dedicated to reducing the carbon footprint of maritime transportation.

- Between 1996 and 2022 the top 20 carriers increased their share of container transportation capacity from 48 to 91 percent. The four largest container shipping companies have once again dramatically extended their market share in the past five years to control more than half of global capacity. The top 4 carriers have market power of 58 percent which can lead to abuse of market power, charging of higher rates and consumer price increases.

- Oversizing of ships is another reason for concern. Between 2006 and 2022 the size of the world’s largest container ships more than doubled from 9,380 TEU (standard containers) to 23.992 TEU. Besides posing problems to some ports and sea lanes, the size of the ships grew faster than the volumes of cargo that filled them. The resulting market consolidation may also lead to a more limited offering as well as higher rates and consumer prices.

- Rising freight rates clearly pose a higher burden on the economies of poorer countries than on those of medium- and high-income countries.

- For 2022, UNCTAD forecasts moderate growth of global maritime trade to 1.4 percent. For the period from 2023 to 2027, annual average growth of 2.1 percent is anticipated, a slower rate than the average of 3.3 percent during the last three decades.