What is smart about the smart city?

Around the world, cities are not only becoming more expansive but, above all, more densely populated as well, so that more and more people are living together in extremely crowded places. At the moment, there are more than thirty megacities in the world with a population in excess of ten million, according to the United Nations. Lagos, the Nigerian metropolis in which some 15 million people are living today, is expected to grow to 80 million by the end of the century. How can technologies help achieve good government and organization of the increasingly complex urban organism?

One response to this challenge – in the much smaller cities of Europe as well – says that digitalization might be able to ensure a smooth and better flow of many processes. Cities have become producers of big data. We not only have more data than ever before but also a wealth of interlinking opportunities. Today, the mass of available data makes it possible for us to access a wide variety of information in urban development contexts such as data pertaining to areas, buildings, the environment and mobility as well as social and economic data.

However, the existence of data alone is no guarantee for success yet. What we need is interactive tools such as data platforms, maps, apps and other forms of visualization enabling data to be interlinked and scenarios to be formed for future urban life. Thinking in terms of scenarios, with which data modeling can help us, is one of the key skills we need to learn more intensively. This is a manifestation of a mindset, creative and complex, scenarios can be developed in a playful manner and with the participation of many players.

At CityScienceLab, we visualize data on interactive tables, among other things. On these tables called City Scopes, which are developed in collaboration with the MIT Media Lab in Cambridge (USA), future scenarios of a city can be modeled very vividly and flexibly. For instance, we can demonstrate what would happen if we reduced the streets for cars in a city in support of more bicycle paths. Using models, we serve as consultants to policymakers and work together with administrative bodies. In a political context, it’s becoming increasingly important to present data in a way that can be understood by as many people as possible. That takes us back to the facts and away from populism and ideology, and makes it easier to talk about concrete solutions.

The intensity of such a new, adventurous urban data culture in the area of urban development varies in individual countries. That’s why the development of new forms of collaboration using digital tools is one of our key research topics and action fields in the area of the digital city. In the city itself as well as among cities. Finland’s capital Helsinki has assumed a pioneering role in the areas of data use, data transparency and networks. We have to make such treasure troves of experience accessible to cities that are less smart in order to benefit from them on a global scale. Whether or not a city is “smart” will decisively have to be measured against the question of whether or not digitalization benefits its people and promotes collaboration between a wide range of players

How do we define a smart city in the context of heavily growing cities? A brief look at the history of the term shows some initial mentions in the nineteen-eighties. The sociologist Manuel Castells described that, increasingly, cities should not be understood strictly as material entities anymore but as networks based on flowing movements of data, knowledge, information and goods. Approaches pursued on the part of industry in particular emphasize increased efficiency and smooth process flows that smart city technologies are supposed to provide for us, for instance through enhanced transportation planning. However, while urban developers attach great value to a smart city becoming more efficient and progressive by means of technical infrastructures, they also stress that it should be designed with more environmental and social sustainability in mind.

“Especially those with the skills of crafting creative combinations and collaborating with machines in elegant ways are smart”

PhD Gesa Ziemer, Head of the CityScienceLab at the HafenCity University Hamburg

Our everyday urban life has long been shaped by digitalization: We use apps instead of analog maps; we rent bikes or cars from sharing or mobility-on-demand systems; we travel using digital booking systems that hardly require us to make travel plans in advance; our local governments are increasingly switching to digital services so that we don’t need to visit a government office to fill out all official forms. Cities are equipped with sensors providing real-time data and residential buildings are increasingly constructed as smart buildings that measure the patterns of how we live. One of the biggest data generators is the mobility sector. A Tesla, today, is already primarily a data collector as well as – albeit just marginally – a means of transportation.

Urban development using digital twins

The construction industry, as well, is increasingly based on data, for instance when using Building Information Modeling (BIM) or Virtual Design and Construction (VDC). BIM describes a method enabling connected construction between the planning and execution stages of a building. All construction data can be captured, combined and modeled with software, which is intended to lead to better collaboration between the diverse disciplines. Today, there’s talk of also linking data from the surroundings such as environmental, traffic and social data with building data so that construction deals not only with the building but also with the consequences of the buildings for its surroundings. This is summarized under the heading “from BIM to CIM,” in other words City Information Modeling. These technologies are sub-aspects of digital twin technologies we’ve come to know from industrial manufacturing and that are now being transferred to cities. In the city’s twin, urban development is supposed to be simulated and predicted before being implemented in the real world.

Digital decision aid

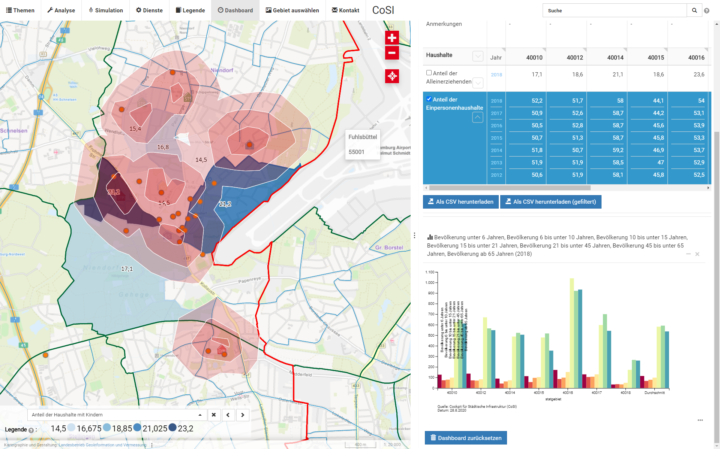

The “Cockpit Social Infrastructure” (COSI) is an application example of smart data combinations. It serves as a digital decision aid for local government employees who are now able to access data centrally from a web-based platform instead of having to send individual queries to various government agencies as in the past. “That employees can independently combine data and make simple calculations in a decentralized way is an immense relief,” says Prof. Gesa Ziemer. The data can be linked independently on a simple interface enabling predictions to be made. If apartments are being built in a particular neighborhood, how many childcare center slots, green areas or retail stores would be needed? If the coronavirus infection rates are particularly high in a neighborhood, where would be the best places for test centers? COSI is a “living” project continually subjected to further development.

The art of smart combinations

Which urban technologies have a pioneering character? Basically, innovation in this context is not so much about inventing something new but about combining in “smart ways” things that exist. Like no other organization, the city is well-suited for this purpose because huge treasure troves of data can be mined and recombined. Based on my daily experience – nationally in Hamburg – I would highlight the following five areas:

- First, every city needs an urban and transparent data platform providing the basis for easy access to data. The pandemic has shown how important it is, also in situations of crisis, to have a solid data management system from which data can be visualized and combined quickly.

- Second, every democratic government must have co-creation systems with the help of which citizens can communicate with their governments. Citizens not only want to be informed but also be actively involved in planning processes.

- Third – especially in the mobility sector – sharing systems are in development. Mobility-on-demand systems combine cars, public transportation, bikes, ships or pedestrian paths to show us the most efficient route in terms of time and/or money – preferably in a single, centralized app.

- Fourth, there’s a growing need for digital planning and construction tools for dynamic and interdisciplinary modeling of future urban scenarios.

- Fifth, around the world, prediction tools that are important for climate protection are in development. Here data pertaining to space, organization, physis, function and time are collected and modeled to enable predictions of future shock and stress moments for cities and regions such as storms and floods as well as political unrest.

Obviously, data security is an important issue concerning all of these items. In my view, controlling an entire city – from transportation to local government to hospitals and energy supply – from a single control center entails an extremely high risk. A horrific scenario would be for all hospitals to suddenly become dysfunctional because of something having been hacked. So, for all developments, corresponding backup systems preventing such scenarios have to be implemented. Generally, I’m in favor of decentralized data systems.

The question of who the data of a smart city belong to is another highly intriguing one. I feel that the city has to try to remain as independent as possible – even when working together with major technology corporations. After all, the city is responsible for providing services and information to its citizens that they need in life – and not to sell technologies.

However, generally speaking, I see that all the parties involved can benefit from collaboration: the larger the volumes of public data combined with those of businesses, the more we’re going to learn about our city, and the larger the number of new business models including startups that can emerge.

All approaches have in common that in spite of the major feats achieved by machines, they continue having to collaborate with people. Therefore, especially those with the skills of crafting creative combinations and collaborating with these machines in elegant ways in the future are smart.

More on the CityScienceLab at: media.mit.edu