We followed by I – followed by illness?

Together we’re strong. That’s what humans, even those living as far back as in prehistoric times, would tell themselves, preferring to place their trust in a collective effort of defending themselves against enemies and looking for food. Besides reflexes and automatisms such as breathing, procreation, or digestion the human need for social contact has anchored itself in the brainstem, the oldest part of the brain from an evolutionary point of view. The information anchored there still decisively controls our behavior. Hence the human tendency to form groups is an innate trait. Consequently, loneliness is something that doesn’t feel right.

The author

André Hajek studied economics and social sciences. Since 2021 he has been Professor of Interdisciplinary Health Care Epidemiology at the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf. His research is specifically dedicated to the causes and consequences of old-age loneliness. He’s convinced that technology can help fight loneliness in major ways. Albeit, he feels, that it’s crucial for every individual to really make use of that potential.

In the realm of research, loneliness is typically viewed as a negative emotion: a subjective discrepancy between desired and actual social relationships. Such subjective discrepancy can refer to the quality as well as to the quantity of social relationships. By contrast, objective social isolation is understood to be a lack of social activities such as club life. Both are typically correlated only in moderate ways. For instance, a person may be lonely but not isolated – and vice versa. By the same token, aloneness should not be equated to loneliness. Hence singles or people living alone don’t necessarily have to be lonely.

Loneliness and isolation research used to live in the shadow of science for a long time. The Covid 19 pandemic – and the social distancing it entailed – put that subject onto everyone’s lips. Now we know that loneliness and social isolation are important issues not only for older people, whose numbers in the world keep growing due to increasing life expectancy, but that they can affect young adults and middle-aged people as well. In 2021, for instance, nearly one in ten people in the industrial nation of Germany felt lonely, according to the so-called loneliness barometer.

Higher percentages were evident especially among 18- to 29-year-olds (14.1 percent). A study conducted in 2022 that referred to the general population aged 16 and older in all 27 EU member countries showed a loneliness prevalence of around 13 percent. The percentages varied between just under 10 (Netherlands, Czech Republic, Croatia, and Austria) and just over 20 (Ireland). Researchers explained those discrepancies between the EU countries to themselves by referring to cultural differences and differences in demographic composition.

The consequences of loneliness and isolation

Loneliness and isolation are frequently referred to as the “new smoking” because these phenomena have very negative effects on physical and mental health. According to the WHO, lonely people have a 50-percent higher risk of developing dementia, the risk of contracting cardiovascular diseases increases by 30 percent. Consequently, it’s only logical that the probability of early death massively increases as well – by as much as 25 percent.

As an additional exacerbating factor, aloneness distorts our perception: lonely people have lower trust in institutions such as the police, legal systems, and policymakers, among other things.

A way out or a trap: digital media

Technologies can build bridges particularly for people whose family or friends live in far-away places or for people living alone and suffering from mobility impairments. A modern smartphone is truly a panacea in those cases. Presupposing a certain affinity for technology, video chats etc. provide users with good opportunities to stay in touch, with smooth transitions to social media like Facebook, Instagram, or TikTok. Some love them and others demonize them but the correlation between social media and loneliness and isolation is not as clear as some might think …

A few years ago, an American study that received a lot of attention managed to establish a correlation between the use of social media such as Facebook or Instagram and subjectively higher social isolation among young individuals between 19 and 32 of age in the United States. The authors attributed that to idealized profiles of other users with apparently many contacts and events, among other things. Looking at such profiles, one soon feels like living a hermit’s life even if, factually, that doesn’t need to be the case. Information in social media referring to events in one’s circle of friends to which one hasn’t been invited can intensify a feeling of isolation.

„My own studies among middle-aged and older people in Germany established an opposite effect, in other words, that older people using social media are less isolated than those that don’t."

André Hajek

My own studies among middle-aged and older people in Germany established an opposite effect, in other words, that older people using social media are less isolated than those that don’t. Imagining that social media make it possible for people to stay in touch even with childhood friends or relatives living in far-away places, which wouldn’t be possible in that way in the case of poor health, those outcomes seem very plausible. A more recent overview on the same subject confirmed that as well.

However, if the use of digital media leads to extreme social withdrawal – the Japanese frequently refer to that as “hikikomori” (“to hunker down”) – loneliness and isolation are default settings. It seems like that’s another example of the dose making the poison.

Gaming: solo combatant or team player?

Computer games can be loneliness drivers or saviors as well. If someone succumbs to the urge of engaging in increasingly frequent and longer gaming sessions there’s little room left for other hobbies and real-world social contacts. Consequently, friends and family might withdraw from that person. But it could turn out the other way around as well: Because an individual is lonely, they escape into the world of gaming to find validation there and become even more isolated. On the other hand, many computer games are so successful precisely because they’re team-based. In that case, gamers avidly chat via their keyboards or headsets – frequently in global networks. No victory without communication, so in terms of interaction, many a computer game is on a par with a classic board game round.

Older groups of the population could find ways out of loneliness via gaming as well. Video games – such as bowling or playing tennis on video consoles like Nintendo’s Wii – thrill even seniors with no gaming experience. Consequently, one could assume protective effects in terms of loneliness and isolation. In fact, games like those have already been investigated in the context of loneliness – albeit relatively rarely and with differing outcomes. While, for instance, an American study among very old people managed to prove a positive effect on loneliness when individuals played Wii Bowling with a second person (compared to a control group watching television with a second person) a second study in Singapore revealed no such effect. Petra Möllecken, head of the Irmgardisstift Süchteln seniors’ home, has certainly had positive experiences in the field with Wii Bowling. In a magazine published by Caritas, she refers to the community spirit emerging during the game and, as another positive effect, to the boosted self-confidence when residents are successful in bowling.

Digital motivation

And what about wearables, the digital body monitors we voluntarily wear as bracelets, rings, and watches, or carry around with us in smartphones? A study specifically dedicated to the peak of the pandemic in June/July 2020 could not establish any direct correlation between wearables and the feeling of loneliness among older people. Even so, those kinds of applications might become increasingly attractive because some providers have identified loneliness as a human problem area, offering wearables that can detect those conditions. Analyzed for that purpose are the number of incoming or outgoing calls and messages or time spent away from home, among other things. Like the message relating to the well-known daily 10,000-step goal, the call to “communicate” might be a promising proposition – unless it should wear off too quickly.

It’s just that the thing about communication isn’t so easy. Especially older people have a hard time establishing new contacts. Experience has shown that multi-generational residential buildings simplify interactions, so having an overall positive effect on satisfaction with life. The idea from South Korea to establish playgrounds for seniors where they can get together and engage in activities is an intriguing proposition as well. Albeit, the best ideas are futile unless people use them. It takes each and every individual to make use of existing opportunities. A reminder by a digital helper can provide the necessary motivation boost.

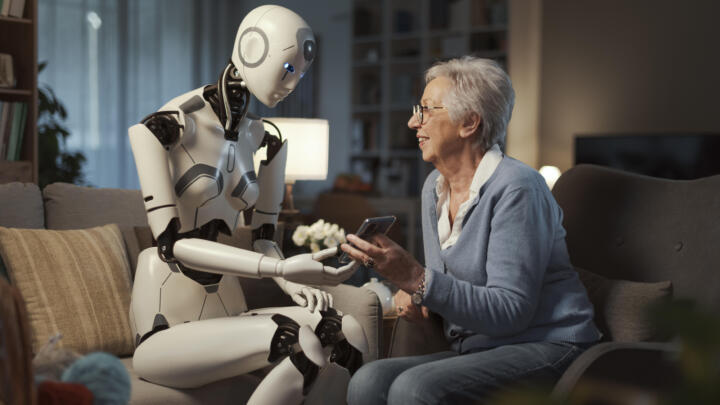

Cuddling with a robo-dog

That pets such as dogs or cats are effective loneliness fighters is generally known. The problem is that they require intensive care and therefore cannot be integrated into all situations in life. Although animatronic or robotic pets resemble our real-world four-legged friends they’re clearly less demanding. Occasional charging is all they need. In senior caregiving settings in Japan, these cute companions are already frequently in use. They’re suitable playmates for children too. Robo-pets can simulate movements, sounds, and sensory responses – such as walking, barking, or even singing. But can they also provide us with social warmth? A few years ago, an American study investigated that question in greater detail. For that purpose, older people (65+) were provided with an animatronic pet of their choice (dog or cat) that was to be treated like a normal pet. The participants of the study filled out standardized questionnaires when they received the pet as well as 30 and 60 days later. In fact, the interaction with the animatronic pets reduced their feelings of loneliness and enhanced their sense of wellbeing. The artificial doggies and kitties were relatively inexpensive, the authors of the study talk about 55 to 110 U.S. dollars, and therefore not highly sophisticated in terms of technology. Another study confirms those experiences: interactions such as cuddling, caregiving, and going to sleep with animatronic pets reduces feelings of loneliness.

In total, research work of the effects of animatronic pets on loneliness/isolation is still in its infancy and the current state is that truly reliable statements about it are not available yet. It can be assumed though that this research gap will be closed soon because ultimately animatronic animals – like robotic nurses – have the potential to noticeably relieve the burden on informal as well as professional caregivers.

When “woof-woof” turns into “hello”

But animatronic pets aren’t the only things to be mentioned because humans’ best friend may be able to increasingly score as a loneliness remedy due to technological progress in the not-too-distant future too. Because what if poodles, dachshunds, and terriers could suddenly speak our language? Progress in AI might make that possible in the future. But with what consequences? Intuitively, one would assume that the supposedly better relationship quality could noticeably reduce loneliness and isolation. But maybe the enhanced clarity of the communication might also lead to more arguments and disenchantment so that we’d be longing for a return of the good old days in which a dog simply barked?

AI could also help bring people that have died back to life – as true-to-life avatars. If enough audio and video data were available that could work by means of artificial intelligence. In that case, a grandson would not communicate with Alexa or Siri but with grandma who’s been buried for a long time. Or in the “Dinner for one” sketch, the lonely Miss Sophie wouldn’t have to sit in a round with empty chairs but could clink glasses and chat with her late companions. A “digital afterlife industry” specializing in precisely those kinds of use cases has long begun to form.

Conclusion and outlook

At the end of the day, what will remain? Technology is a two-edged sword for loneliness and isolation. Hiding in cyber worlds from real life can clearly be conducive to loneliness and isolation. Used “beneficially,” reasonably applied technologies do have the potential to mitigate loneliness and isolation. That potential seems to be very large for older people, especially when the generation that grew up with digital technologies (digital natives) will have reached retirement age.