A journey into the unknown

Embarking on a journey by car at the beginning of the 20th century is a bold undertaking. Paved roads are practically non-existent, nearly all of the rural roads are dirt roads full of potholes, or just trails, and the number of bridges can almost be counted on the fingers of one hand. Although the automobile invented in 1885 is becoming increasingly popular it’s still a far cry from being a means of mass transportation. About 8,000 cars exist in the United States in 1900. By 1910 their number will have grown to nearly 460,000. Twelve years later – while horse-drawn carriages can still be seen in the streets of New York City – vehicles are surpassing the one-million mark for the first time, not least thanks to the Ford T-Model, the first mass-produced automobile. For comparison: today, more than 260 million cars are traveling on U.S. roads.

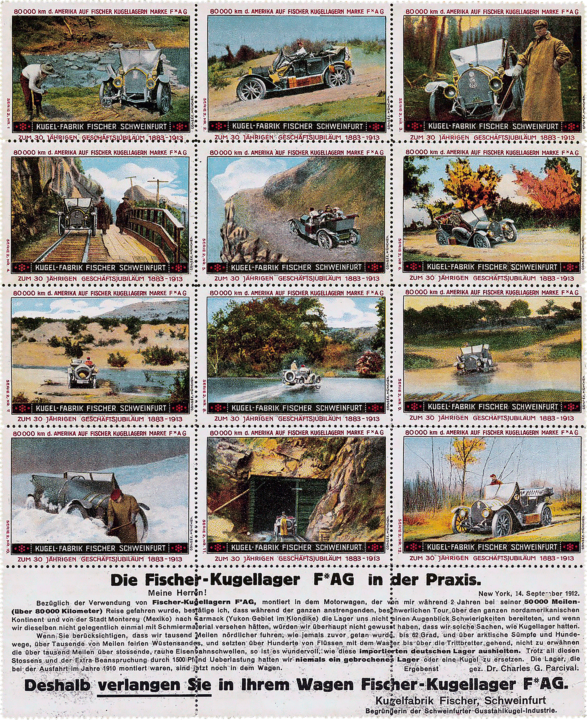

When in 1910 journalist Dr. Charles G. Percival, then a writer for the New York monthly magazine “Health,” has the crazy idea of crossing the United States in an automobile – from south to north and from east to west – the traffic routes for motorized vehicles are not at all designed for such an endeavor. That same year, though, the adventurer, who has also been working as a war reporter, physician and geologist, embarks on his big journey in Monterrey, Mexico. Ultimately, it will last nearly two years and take him across a distance of some 50,000 miles (more than 80,000 kilometers). His vehicle, a 30-HP Abbott-Detroit which Percival has affectionately nicknamed “Bull Dog,” is hopelessly overloaded. The adventurer has just packed anything he believes might be of use to him on his trip: fuel cans, food, a tent, a fishing rod, plus a pistol and a camera with which he meticulously captures his adventures.

Huge strain on humans and hardware

Percival, accompanied by mechanics taking turns doing their stints, goes to the hilt. In California’s Imperial Valley, he drives 50 meters (164 feet) below sea level and in the Rocky Mountains, climbs to an elevation above 3,300 meters (10.826 feet). In Alaska, he travels beyond the 62nd parallel – no automobile ever having gone as far north before. It will take until 1978 for another car to arrive there – after a highway has been built. Especially the routes there and in the Canadian Yukon region are grueling. Time and again, Percival and his crew get stuck in the mud of fall that has set in by then. Hungry and frozen, they’ll spend hours digging the ground to free the car, cutting trees in order to use their trunks to fortify the trails. At times, they only advance a few miles per day while being exposed to the elements in the open-top “Bull Dog.” For lack of negotiable trails, they often drive on railroad tracks.

Percival attracts attention wherever he stops on his journey. As he regularly writes articles for newspapers during his trip, Americans are kept abreast of his progress. Percival becomes a crowd puller whenever he arrives in town. During his trip, he meets with then U.S. president William Howard Taft, some 40 governors and countless mayors. Students are released from school because they want to take a close look at the visionary and his vehicle, often following it on foot for miles. After his return, Percival adeptly goes about marketing his trip. He writes a book in which he acknowledges and thanks his numerous sponsors and suppliers. One of them is today’s Schaeffler brand FAG with whose wheel bearings Percival’s Abbott-Detroit was equipped and which “caused not a single moment of problems.” In 1999, historian James H. Ducker writes about Percival’s work that it was “the reminder of a quiet revolution (...) [that] would doom some railroads and drive others to the brink, raise up a new industry concentrated in Detroit, and greatly reshape the geography and the lives of Americans.” It marked the beginning of the automotive revolution.

Auto adventures

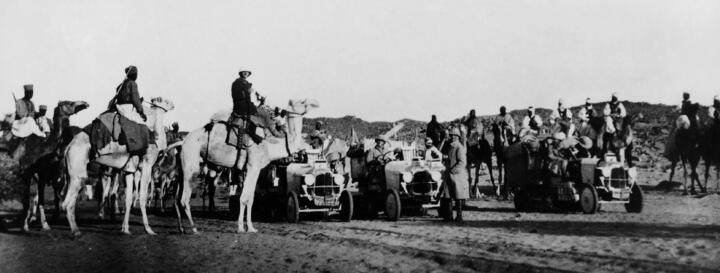

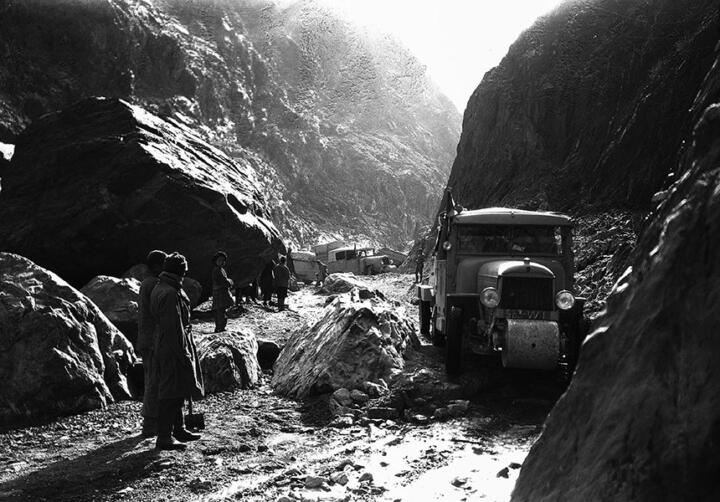

Percival was repeatedly followed by others embarking on great adventures in automobiles. One of these pioneers was the Frenchman André Citroën whose expeditions were primarily aimed at enhancing public awareness of his brand. In 1922/23, his tracked vehicles were the first to cross the Sahara. Subsequently, he initiated the “Croisière Noire” (Black Cruise) on which the participants in 1924/25 covered a distance of some 28,000 kilometers (17,398 miles) across Africa from Algeria to Madagascar and six years later the “Croisière Jaune” (Yellow Cruise) through Central Asia. The latter, however, had to be stopped after crossing the Himalayas because the expedition’s leader, Georges-Marie Haardt, died of pneumonia during the trip. At the same time, the German Clärenore Stinnes caused a sensation. From 1927 to 1929, she was the first person ever to circumnavigate the world in a passenger car.

But even today, a zest for adventure still manifests itself now and then. In 2007, the then co-presenters of “Top Gear,” Jeremy Clarkson and James May, ventured out into ice and snow and were the first to reach the magnetic North Pole in a car. In 2009, the German Rainer Zietlow at the “EcoFuel-Panamericana” covered a distance of some 50,000 kilometers (about 31,000 miles) in a natural gas powered VW Caddy in North and South America with stops including Schaeffler locations in Brazil, Argentina, Mexico and the United States.