The digital high in the north

Harald I, called Bluetooth, was a bully. He was king of Denmark and Norway in the 10th century and, like many of his Viking ancestors, enjoyed invading other countries, Normandy on particularly frequent occasions. But on the other hand, he also initiated the christianization of Scandinavia and united the northern countries that today are known as Denmark, Norway and Sweden. He overcame boundaries and established new connections – and that’s exactly why the inventors of Bluetooth technology named the globally used standard after the old king. His initials, H and B, in runic script, are perpetuated in the Bluetooth logo. Bluetooth was developed for the Swedish telecom giant Ericsson. Its Finnish neighbor and competitor contributed know-how as well. An ICT milestone made in Scandinavia – just one of many.

Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland are digital hotspots not only with reference to Europe. The same applies to their global ranking. In a study, the World Economic Forum has rated Finland, Sweden and Norway behind Singapore in positions two, three and four of the countries best prepared for the digital challenges of the future. The EU Commission has identified Denmark as a “digital leader” – trailed directly by Norway and Sweden.

Cables laid early even to the remotest corners

What makes the northern countries so strong in terms of bits and bytes? How does their digital expertise affect everyday life at home and at work? Nobody becomes leader of the standings overnight, neither in sports nor in the world of ICT. There are many reasons why the Nordic countries are in such a good position today, a major one being a close-meshed telephone and broadband cable network. Much earlier than most other countries in the world, the Scandinavians began to establish networks to connect with even the farthest reaches of their countries – and there are plenty of remote places in the rather sparsely populated north of Europe. In Denmark today, according to the Digital Economy and Society Index 2016 (DESI), 92 percent of the entire population have access to a high-speed line with a minimum of 30 Mbps. Norway (80 percent) and Sweden (76 percent) are above the European average (71 percent) as well. In addition, Sweden shines with 99 percent LTE4 coverage. In spite of extremely low cable fees, the Finns tend to prefer cell phones. In the country that’s home to former cell phone world market leader Nokia, there are 139 cell phone contracts per 100 citizens, nearly twice as much as the European average. Land lines, if at all, can only be found in offices anymore, particularly in Finland.

Nokia’s comeback gains pace. Lifting spirits in Finland

Olli Rehn, Finland’s Minister of Economic Affairs

Talking about Nokia: The Finns, presumed dead by many, quit the smartphone business, but by acquiring a competitor have become the world’s largest supplier of network technologies, relegating their Swedish rival Ericsson to second place. Due to their strong presence in their home countries, Nokia and Ericsson with their more than 100,000 employees have contributed a lot to the population’s affinity to technology and innovations. U.S. web pioneer Ajaz Ahmed thinks that the digital pioneering spirit at the Polar Circle is certainly “comparable with the one in Silicon Valley.” Driven by similar curiosity and zest for exploration that made their ancestors, the Vikings, set sail for unknown coasts, young northerners embrace new technologies.

The end as a hotbed for something new

Needless to say, Nokia giving up its smartphone business was a blow to the Finnish soul. But: Many of the employees who lost their jobs as a result ventured the leap into self-employment and founded start-ups. These, too, contribute to the fact that in Finland, today, 6.7 percent of all jobs are in the ICT sector. Not surprisingly, on a European scale, only Sweden (6 percent) can match up to this, the European average being 3.7 percent. Ex-Nokians have since bought back the naming rights of their old company for mobile end devices from Microsoft and are planning to soon start selling smartphones and tablets bearing the Nokia logo. “Nokia’s comeback gains pace. Lifting spirits in Finland,” said Minister of Economic Affairs Olli Rehn on Twitter, assessing this development. The “old” Nokia on the other hand has found new fields of activities, such as digital medicine applications and cameras for virtual worlds.

Finland is Nokia, and Nokia is Finland – one might think. However, Finnish ICT outfits are also particularly present in the games market. Rovio, a company founded in the Espo suburb of the country’s capital in 2003, with “Angry Bird” has landed a worldwide hit that was a chartbuster also as a motion picture. Although the bird fever has notably cooled down and a sequel has not yet been launched, the dream of becoming the 21st Disney continues to exist. Another heavyweight in this scene is games developer Supercell (“Clash of Clans”) from Helsinki that was founded in 2010 and, today, has a market value of several billion euros.

Helsinki also plays host to Slush every year – a type of Woodstock of the start-up scene. “The event is currently the universe of the tech scene,” says Niklas Zennström, co-founder of Skype and Atomico. It’s not only a place where 2,000 start-ups meet, but also 800 venture capital firms whose money might propel innovations into the next orbit.

That the Nordic countries have produced such an active and innovative start-up scene is not only due to their enthusiasm for all things digital, but also due to the close-knit social network that catches bold entrepreneurs in case they should occasionally stumble. Another typical aspect in the north of Europe is a society shaped by co-determination and flat hierarchies. “The way in which Nordic companies operate can be linked with the sauna culture,” said Jean-Jerome Schmidt, Head of Marketing at ICT services provider Severalnines, in a report on techradar.com. “Whether you’re the CEO of a company or the receptionist, once you’re all sitting in a sauna together, barriers fall and everyone is at the same level.” Pär Hedberg, Chairman of Swedish hardware supplier THINGS, adds: “The intern’s ideas are given as much respect as the CEO’s, and a culture like this fosters genuine innovation.” Not least due to this culture, Sweden has not only produced H & M, Ikea and Volvo, but also global digital success stories like Skype, Spotify, MySQL or “Minecraft.”

Open mind, open data

Across companies, creative interaction is appreciated as well. The Linux operating system of the Finn Linus Torwalds is a prime example of the openmindedness of Nordic ICT companies. Whereas Microsoft and Apple guard the source code of their operating systems like a gold treasure, a worldwide developer and user community keeps improving the functionalities and possible uses of Linux.

Such openness is by far not the exception in the digital north. Neil Sholay, Vice President of Digital, Oracle EMEA, reported having observed how closely start-ups work together there, creating a very innovative community. A close-up experience of this can be gained in the Kista Science City in the north of Stockholm. More than 1,000 companies of the industry, including big players like Microsoft, IBM and, of course Ericsson, have set up operations in Europe’s largest ICT complex. This is where wireless communication standards such as NMT, GSM, EDGE and W-CDMA have been developed.

Access to open public data leads to new services, entrepreneurship, business development and a more open and democratic society. Giving others access to these data can create added value for the whole society

Jan Tore Sanner,

Norway’s Minister for Local Government and Modernization

When it comes to handling data, a certain openness is valued as well. In Finland, for instance, sending a text message is all it takes to identify the owner of a vehicle. The personal incomes of individuals can be viewed by means of just a few mouse clicks as well. When the Google Car drove through Copenhagen, Goteborg or Helsinki to take Streetview pictures it wasn’t accompanied by a firestorm of protest, as had been the case in Germany for instance. Is so much data nudism good or bad? Obviously, this is debatable. For Jan Tore Sanner, Norway’s Minister for Local Government and Modernization, it’s clear: “Access to open public data leads to new services, entrepreneurship, business development and a more open and democratic society. Giving others access to this data can create added value for the whole society.” Nonetheless, Norwegians basically feel that every individual should be in control of their personal data.

In Denmark’s capital Copenhagen, in collaboration with the Japanese electronics corporation Hitachi, the database platform “City Data Exchange” is currently in the making which, if successful, might also be used in other big cities. It’s intended to bring together all segments of society – authorities as well as citizens and companies – who will have access to the database. Be it statistics about energy consumption or crime rates, environmental data or the current weather forecast, surveys or real-time measurements: the data cloud above Copenhagen is growing. Target group-specific applications – ideally developed by local start-ups – help analyze the data.

Like Norway’s Minister Sanner, Copenhagen’s Lord Mayor Frank Jensen is convinced that good access to data provides many positive impulses, “which among other things, can create new technological solutions. For instance developing applications to save energy and increase mobility for companies and citizens. Innovative solutions can also help foster growth and create jobs in Copenhagen,” he says.

Investment in research and education

Respective investment in research and education is another factor that plays a role in extending the digital advantage the northern countries have achieved. At the moment, the north of Europe is suffering from a shortage of ICT specialists. One of the reasons being that after the internet bubble at the beginning of the millennium burst, many young people starting college opted for other fields. To avoid such inhibiting shortages of personnel in the future, young people are to be familiarized with the digital worlds early and on a broad base. This is another reason why educational authorities in Scandinavia recently teamed and linked up with New Media Consortium (NMC), a global community of leading universities, colleges, museums and research centers. The objective is to inform school principals and other decision makers in the field of education about the latest technological developments and, in the next step, integrate them into the classroom. In the next five years, it is planned to include cloud applications, the Internet of Things, computer-based simultaneous translation and wearable technologies such as Google Glass, smartwatches, body sensors and even computer games in the curriculum. Even at this juncture, the Scandinavian countries are trailblazers in terms of online learning aids and tests. Notably, universities and ICT firms are closely interlinked. In many cases, these companies set up sites close to the campus or assign employees to teach at the universities. The Kista Science City alone has established teaching positions for 6,800 students at the university and technical university in Stockholm.

An exciting project is supported by the non-profit organization “Ung Företagsamhet” (“young entrepreneurship”) in Sweden, in which high school students between the ages of 16 and 20 years can start a company of their own alongside their classroom work. The reported successes are respectable, indicating that the participants have enhanced their self-confidence, decision making and team skills. In addition, they’re said to be better at problem solving.

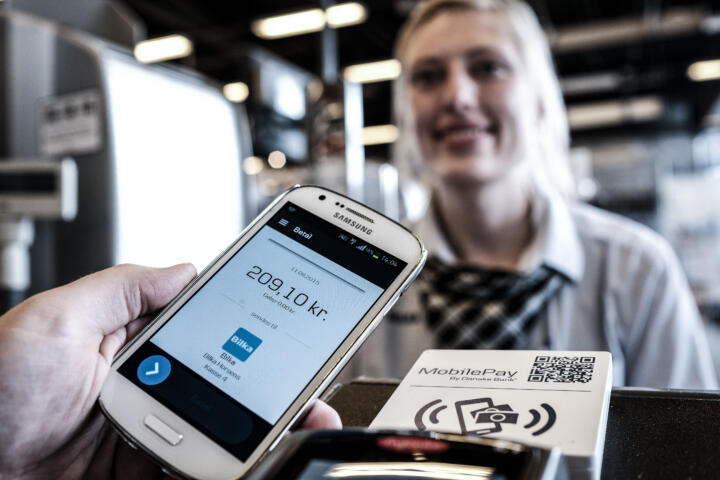

The northern countries’ affinity to technology is reflected in everyday life as well. Be it shopping, banking, communication with authorities and doctors, or mobility applications: there’s hardly another region in the world where everyday needs are being met by online services to an equally great extent. Sweden, the country that, about 350 years ago, was the first to introduce banknotes, is now about to assume another monetary pioneering role: by completely abolishing hard cash. Since 2008, the circulation of hard cash has been cut in half in the kingdom. Getting one’s hands on it has meanwhile turned into a real challenge, as more than half of the branch banks have stopped disbursing coins or bills. Getting rid of them again is no mean feat either because not only the Stockholm subway insists on electronic payment. Even at flea markets in the north of Europe, people increasingly make cashless payments – thanks to MobilePay. The system initiated by the Danish Danske Bank even makes transfers possible from one smartphone to another. Times change, and so does money: cash is no longer king – only if it comes in digital form.