Rolling through the ages

Before we turn to the pre-Christian period that marked the birth of the rolling bearing, let’s take a quick look at Schaeffler’s company chronicle. In 1883, Friedrich Fischer whose company, FAG, subsequently becomes part of the Schaeffler Group invents the ball grinding machine. The machine makes it possible to manufacture large volumes of hardened steel balls by grinding them to absolute uniformity and roundness. Thanks to Fischer’s invention, the ball bearing sets out from Schweinfurt to become a worldwide success. A vehicle that immediately benefits from this innovation in a major way is the bicycle, with the automobile following in its slipstream.

Fischer and his even more ingenious precursor

The ball bearing that achieves its breakthrough as a mass-produced product with the help of Fischer’s machine can be traced back to a man who’s arguably humanity’s greatest polymath: Leonardo da Vinci. The equally sophisticated Renaissance artist, well-read scientist and visionary designer experiments with a wide variety of devices – from hydraulic machines and martial armor to bridges and transmissions, through to helicopter-like flying machines: 500 years ago, mind you. In his experiments, da Vinci keeps encountering the physical issue of friction and around 1490 makes a drawing of a device that is to remedy this problem. The idea of what we define as a ball bearing today is born. Da Vinci fixes in place freely moving balls inside an enclosure without them touching each other, a measure that reduces friction even further. However, as da Vinci uses hardwood for the balls, there are deficits in terms precision and durability. The first ball bearing application based on da Vinci’s invention can be found in so-called post mills where the bearings help turn the entire body of the mill that houses the machinery to bring the sails into the wind. Da Vinci himself uses his ball bearings for exploratory drilling projects.

Who invented it? Leonardo da Vinci, of course. The more than 500-year-old picture shows a sketch of a ball bearing by the universal genius

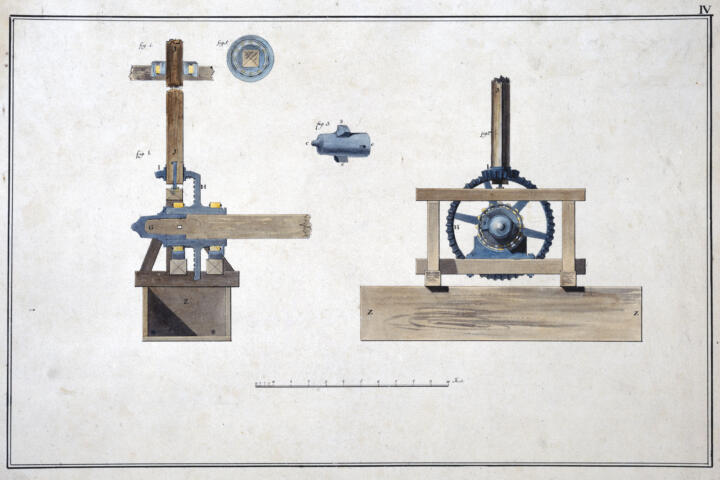

In 1883, Friedrich Fischer by inventing his “ball mill” paved the way for the rolling bearing to becoming a product that would be mass-produced by the billions

The first ball bearing patent though was awarded to the Welsh inventor and ironmaster Philip Vaughan in 1794 which he had filed under the title “Iron ball bearings for carriage wheel-axles.” Vaughan casts the balls from molten iron. Individually made by hand, they are a far cry from the precision achieved by Fischer with his ball grinding mill but, at least, Vaughan’s iron balls were clearly more durable than da Vinci’s wooden ones.

Back to antiquity

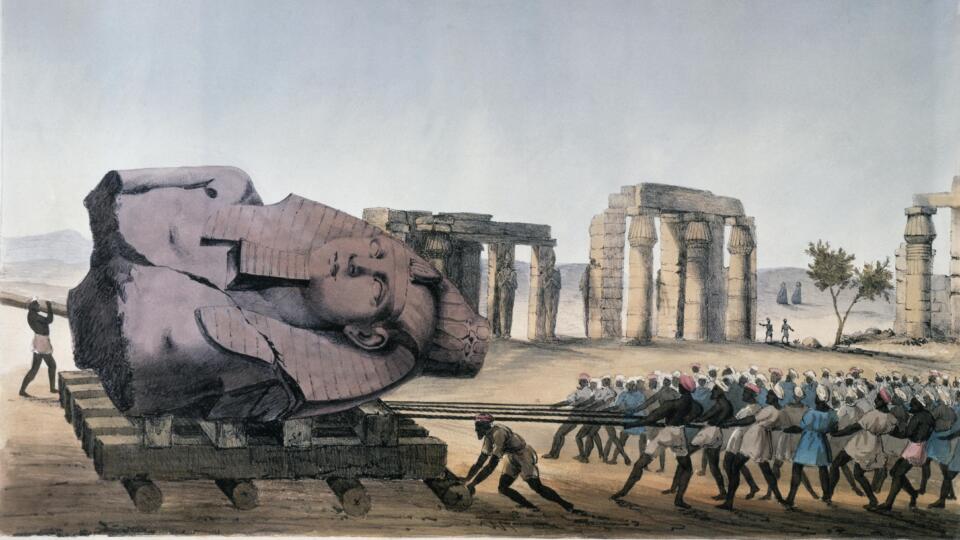

Rolling bearings, though, existed long before da Vinci and Vaughan. How long is a subject of debate between scholars. Antique drawings show that the Ancient Egyptians and Assyrians already used logs as rolling bearings to move heavy monoliths and sculptures. Probably even earlier, humans discovered another way to reduce friction and, as a result, to facilitate motion and reduce wear: lubrication. Again, it’s drawings from Ancient Egypt that show water being poured in front of heavily laden cargo slides to make it easier for them to glide.

The principle of plain bearings for rotating objects is about as old as the invention of the wheel, in other words some 5,000 years. To reduce friction, heat and wear, tallow, earth pitch, resin or bee’s wax is spread across the mating surfaces. A first wheel guide using a type of rolling bearing was discovered by archeologists on a Celtic chariot that is about 2,700 years old, with beech-wood sticks rolling between the axle and the wheel providing a bearing.

Once again, it’s Leonardo da Vinci who’s the first to scientifically investigate friction and to note down physical laws that are still valid today. In 1493, he notes in a sketchbook that the force of friction between two sliding surfaces is proportional to the load which pushes the surfaces together. The size of the contact area between the surfaces is immaterial if their weight is identical. Furthermore, da Vinci recommends the use of bearing bushes consisting of 70 mass percent tin and 30 mass percent copper – a similar mixing ratio as that of white metal that’s still being used in plain bearings centuries later.

Modern plain bearings do not require oils and greases as lubricants. Instead, surfaces made of sliding materials such as Elgoglide and Elgotex developed by Schaeffler or the metal-polymer composite E40 ensure low-friction operation. The use of plain bearings is recommended for applications involving high rotational speeds, small radial or axial assembly spaces or – due to their good absorption properties – vibrations and shocks. Applications for Schaeffler plain bearings span a very wide range, from automobiles to trains.

A major advantage of the plain bearing is its simple design, which is why it eclipses the rolling bearing for a long time. Innovations like Fischer’s grinding machine simplify and reduce the cost of manufacturing rolling bearings – a game changer. In addition, benefits such as lower friction and maintenance requirements help make the rolling bearing a mass-produced product.

The ball and the cylinder have long been joined by other forms of rolling bearings. In 1898, Henry Timken files a patent in the United States for the tapered roller bearing. The barrel and the thinner needle are other forms of rolling bearings. In 1907, the Swede Sven Gustaf Wingquist invents the spherical roller bearing. Developments never stop and if something is not a new invention it’s at least an improvement. In 1949, a certain Georg Schaeffler, for instance, while driving through the country, has the idea of individually guiding the needles of a roller bearing in a cage parallel to the axis. This makes the bearings more compact and able to resist higher rotational speeds – perfect for installation in automobile transmissions for example.

Caution counterfeits!

On their way into the scrap press: Schaeffler has fake spindle, spherical roller, ball and needle bearings confiscated and scrapped by the tons again and again, and consistently tracks counterfeiting activities and the sale of pirated rolling bearings around the globe. In addition, Schaeffler Aftermarket has established a multi-level security system with codes and labels enabling high-grade original parts to be more effectively distinguished from cheap copies and counterfeits.

“Ever new things to do”

Today, visitors to the website of the company bearing Schaeffler’s name will find more than 30 different types of bearings listed there in thousands of variations. The portfolio for instance includes angular contact ball bearings, spindle bearings, spherical roller bearings, axial deep groove ball bearings or linear plain and rolling bearings. Applications extend from a tiny bearing rotating at 100,000 rpm for dental drills to giants weighing several tons such as the bearing that keeps London’s Millennium Wheel spinning. In the light of such a large breadth of applications it comes as no surprise that the number of bearings required around the globe is in the range of billions. In a single passenger car, over 100 bearings are installed, quietly and inconspicuously performing their duties there as well.

2,700,000 km (1,677,702 mi)

Perfect examples of heavy duty and long life: FAG tapered roller bearing units like this one have been operating in the cars of the Istanbul Metro since 1987. Their mileages have long surpassed the seven-digit mark.

Even in an increasingly digitalized world, bearings have stood their ground. Equipped with sensors, they provide a connecting link between mechanical systems and electronics. In this new role, they no longer enhance the efficiency of motion strictly by reducing friction. Schaeffler, for instance, offers sensor bearings for remote condition monitoring. They make it possible to detect impending defects before they result in costly machine failures and downtimes. In addition, maintenance intervals can be calculated more precisely and therefore more cost-efficiently due to the data collected. As busy data gatherers, sensor bearings are important elements in integrating machines in the age of smart factories, aka Industry 4.0. This data can be used to make production processes flow smoother. In mobility for tomorrow, specifically for automated driving, sensor bearings provide information for car-to-car communication and for service providers. At the same time, mechanical bearings have to be prepared to tackle the new demands of increasing electrification with new specifications.

A phrase coined by Georg Schaeffler that he’d occasionally use in jest perfectly fits the storied development of bearing technology that has been going on for thousands of years. The company’s founder translated the INA brand name – actually an acronym for “Industrie-Nadellager” (“Industrial Needle Bearings”) – to mean “immer neue Aufgaben” (roughly in English: “ever new things to do”).