Out of office

Working in weightlessness

More on austronaut Christina Koch

The astronaut: Working in weightlessness

This woman is really out of this world. Since March 19, 2019, U.S. astronaut Christina Koch has been working in and on the ISS space station. In October, the electrical engineer made space exploration history. Once again, one might add, because the 40-year-old holds the record of a woman’s longest stay in space to date.

-

© NASA

-

© NASA

Christina Koch has four spacewalks under her belt. Together with her colleague Jessica Meir on the fourth one, she made space exploration history

Now Koch is even part of the first all-female spacewalk crew. Following three previous extra-vehicular activity (EVA) missions accompanied by a male astronaut, Koch on her fourth one left the ISS together with her colleague Jessica Meir. The two astronauts replaced a charge/discharge unit for lithium-ion batteries supplying the solar array with electric power. In an interview before the all-female mission that made worldwide headlines, Meir had commented, “The nice thing for us is we don’t even think about it on a daily basis. It’s just normal, we’re just part of the team …”

H20 in her genes

More on marine biologist Antje Boetius

The marine biologist: H20 in her genes

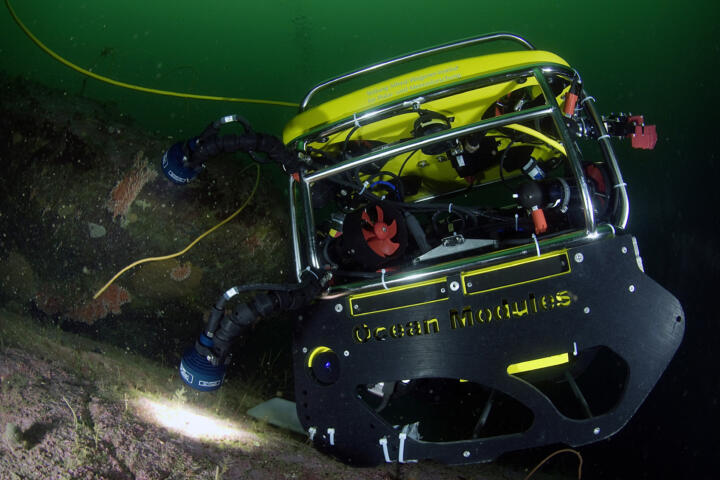

Her grandfather was a captain and whale catcher and as a child she was fascinated by the films of Jacques-Yves Cousteau or Lotte and Hans Hass – with a personal history like that, maybe you’ve got no choice but to pursue a marine career. Antje Boetius is a deep sea explorer, although that description falls a little short of her professional scope: Since November 2017, the 52-year-old has been at the helm of the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven with branch offices in Potsdam and on the islands of Helgoland and Sylt – with a total of 1,250 employees, In addition, Boetius is a professor of geo microbiology at University of Bremen and leads a research team for deep sea ecology and technology at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology.

-

© Mario Hoppmann/Alfred-Wegener-Institut

-

© Mathias Hüne/Alfred-Wegener-Institut

Be it on board of the German research vessel “Polarstern” or a submarine: deep sea researcher Boetius feels at home both under and above water. Her grandfather survived the sinking of three ships

During her professional career, she has led nearly 50 expeditions, spent several years at sea in total and performed several deep sea dives. Just 150 years ago, it was assumed that it was impossible for any life to exist between four to eleven thousand meters (14,000 to 36,000 feet) below sea level. Far from it, as the deep sea is home to millions of species. Nobody can exactly tell how many. “There have been fewer people in the deep sea than in outer space,” says Boetius. She describes diving into this alien world like this: “At the top, sunlight shines through the ocean layers. That’s when you can see all kinds of hues of blue. Once you’ve arrived at a depth of 400 meters (13,000 feet), you’re floating in total darkness.” When the onboard lamps are switched off you can see the glow of luminescent bacteria, fish and jellyfish. The researcher describes this spectacle as “fireworks in the dark.”

Tiny dust particles, huge bearings

More on field service engineer Michael Wernke

The field service engineer: Tiny dust particles, huge bearings

Americans like to give nicknames to their states. Arizona’s is the “The Copper State” – due to its ample copper deposits. Michael Wernke is one of the people who help mine the precious metal. About four times a year, the Schaeffler field service engineer roams the remote, Martian-like landscape of the region in order to provide crucial assistance to his customer Freeport-McMoRan in Morenci, Arizona’s largest copper mine. Morenci is home to the world’s biggest high-pressure grind roller for ore. To enhance the mine’s productivity, Schaeffler developed the first sealed pendulum-type rolling bearing of this dimension – a solid unit with an outer diameter of nearly two meters (6.5 feet).

-

© Schaeffler

-

© Schaeffler

This behemoth is part of Wernke’s scope of responsibilities. The day in his “outdoor office” begins with a one-hour drive into the dusty mine region where a whole army of humongous machines is untiringly doing its work. The impressive grind roller with the no less impressive Schaeffler bearing is one of them. The huge component, which is sealed due to its extremely dusty work environment, initially posed an intriguing challenge to Wernke: how can you measure the clearance of a bearing whose rollers are the size of soccer balls and each of them weigh 50 kilos (110 lb)? “This component is a lot bigger than anything I’ve ever worked on before,” says mechanical engineer Wernke almost with awe. His gift for technical things was obvious at an early age: just three years old, he dismantled the family’s vacuum cleaner! Now the man who’s 1.93 meters (6.3 ft) tall dismantles bearings that are as big as he is.

His motto: “Flat-out or not-at-all”

More on stuntman Erich Glavitza

The stuntman: Flat-out or not-at-all

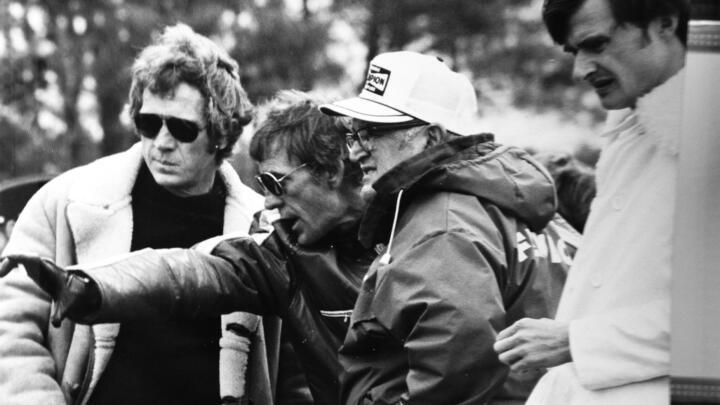

His work area often pushed the limits. “I’ve got no problem with rollovers.” Even so, Erich Glavitza, the man who said this, is now 77 years old. The Austrian’s work was often that of a daredevil but never suicidal. In his book “Vollgas oder nix: Meine wilden 60er mit Jochen Rindt, James Bond und Steve McQueen” (“Flat-out or not-at- all, my wild 60s with Jochen Rindt, James Bond and Steve McQueen”), all-rounder Glavitza describes his wildest rides and most unusual jobs. In the James Bond movie “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service,” he also did the stunts for Bond Girl Diana Rigg. No problem for him: “Actually, I only had to put on a fur hat.” Even though he worked with no holds barred in various movies, he doesn’t call himself a real stuntman. To be honest, he says, he only did on the set what he’d been doing all along: driving cars.

-

© Dr. Erich Glavitza

-

© Dr. Erich Glavitza

For his movie, lead and producer Steve McQueen was looking for a stuntman who was good at crashing: Glavitza

The man who has a PhD in philosophy started racing cars in his youth and later motocross as well. Plus, he worked as a driving instructor. However, he also founded a company, Stunt Limited, together with a partner, Peter Huber, and worked on the set of “Le Mans,” the race driver movie which the lead, Steve McQueen, produced himself in 1970. “He was looking for someone who was able to crash realistically,” says Glavitza, who had this kind of skill. “You have to drive with precision down to an inch for this.” Discipline, he says, is essential to high-precision driving. Glavitza, who also did the stunts for McQueen’s opponent Siegfried Rauch, adds: “Of course that was dangerous. We went full speed. There was no such thing as slow turns and slow motion. Rolling over, crashing into walls – you do things like that when you’re young and dumb.”

Big picture of a small world

More on train operator Lars Rösenberg

The train operator: Big picture of a small world

1,040 digitally controlled trains, 15,715 meters (51,560 feet) of track length, 3,454 switches, 1,380 signals, 9,250 cars, 52 aircraft: and all this on 1,499 square meters (16,135 square feet) at “Miniatur Wunderland” (“Miniature Wonderland”) in Hamburg, the world’s largest model railroad display. What seems like a playground to some is a normal place of work for Lars Rösenberg. He’s a master industrial electrician and in charge of system control. The railroad operation, as Rösenberg calls it, encompasses everything from moving trains to cars to marine traffic. 45 people work on his team, albeit not all of them full-time. “We’re responsible for ensuring that everything rotates and moves,” says Rösenberg.

“Miniatur Wunderland” is one of the main attractions in the port city of Hamburg – and a highly fascinating workplace for Lars Rösenberg

The tourist attraction is open seven days a week. Every morning, the system has to be rebooted, which takes between 30 and 45 minutes – the most critical phase of the day. Rösenberg: “You have to watch how smoothly the system reboots, where faults appear or if a computer crashes.” How he got this job? Very simple: Two weeks after completing his apprenticeship as an electrical technician, he privately visited “Miniatur Wunderland” – and decided to ask for a job. He was only 21 at the time. During the job interview, the electronics chief asked him if he had a model railroad at home. When he said that he didn’t, he got the job. The reason is that a fascination with model railroads is one thing and a highly professional technology standard another. If you ask the 38-year-old today what the best thing is about his job, he pauses for a while and then shouts: “It’s awesome! We keep such a mass of things in motion – and it’s a miracle that it works.”

For her, there’s no such thing as “can’t be done”

More on polar scientist Amy Hobbs

The polar scientist: For her, there’s no such thing as “can’t be done”

Sitting in Antarctica for months on end – that’s something you have to enjoy. Amy Hobbs does. She’s done two stints as the lead service engineer at Casey research station, an Australian research outpost on the Budd Coast in East Antarctica: one in summer (2017/2018) and one in the bitter-cold and dark polar winter (2019) when average temperatures on the coast are between minus 20 and minus 30 degrees centigrade (–4 and –22 °F). However, be it in summer or winter: survival in Antarctica is not possible without proper technical equipment.

-

© Amy Hobbs

-

© Amy Hobbs

Super climate at Casey Station: Amy Hobbs and her team make sure of that by taking good care of the technology as a well-gelled crew

Keeping the technology in good repair is the job of Amy Hobbs and the team she leads. Hobbs is a woman for all seasons. “Working in an amazing environment with a great bunch of people, and having a laugh, even when the task at hand might not be the greatest. I help out the plumbers occasionally,” says Hobbs, describing the work at Casey Station and what makes it special. And what does she do after hours? That’s when the Australian enjoys the constantly changing light on the icebergs and on the sea at Newcomb Bay: “I don’t think I’ll ever have my fill of it,” she says.

Grassroots support

More on parts explainer Himmat Singh

Der Teileerklärer: Immer dicht am Mann

The places he works at are no clinically clean garages in glass palaces. Himmat Singh’s grassroots explanatory work is performed in places that smell of oil and gasoline. For three years, he’s been traveling across the Indian state of Rajasthan for Schaeffler’s Automotive Aftermarket unit. His mission is to inform the garage pros who frequently work outdoors or in thin corrugated iron shacks of the advantages of clutch systems, transmission and suspension components made by the German supplier and to provide them with tips on how to install them.

-

© Schaeffler

-

© Schaeffler

India is an emerging market. The automotive aftermarket there has grown by an annual 14 percent just in the past five years. “The interaction with the mechanics helps me gather feedback on our products. At the end of the day, it’s all about customer satisfaction,” says Singh.

Precision in wood cutting

More on helicoper pilot Wolfgang Jäger

The helicopter pilot: Precision in wood cutting

Wolfgang Jäger is not just flying around for fun. He trims trees and branches with his helicopter – whenever they protrude into train tracks, power lines or ski lifts. Jäger is just one of two pilots employed by the Austrian company Wucher Helicopter who are allowed to fly with a saw. Obviously, this is not a run-of-the-mill cutting device but a long system of linked aluminum tubes from which a 600-kilogram (1,320-lb) circular saw with up to ten rotating sawblades is suspended. The control cable from the saw is routed through the linkage to the cockpit from where the system is controlled.

-

© Wucher Helicopter

-

© Wucher Helicopter

An infernal pendulum: anything that gets in the way of the flying saw with ten rotating blades is pulverized – so pilot Wolfgang Jäger has to fly with proper caution

For emergencies, Jäger’s control stick has a button with which the saw can be released, for instance when it hits an overhead power line. Extremely close teamwork is necessary to keep this from happening. The pilot is engaged in a constant exchange with a co-pilot and a control person on the ground. Jäger: “This is enormously important because on these missions, you have to fully focus on the saw. This involves a lot of high-precision work: it’s not uncommon to cut something just at a 30-centimeter (1-foot) distance from a power line.” If this weren’t difficult enough, it’s also possible for the saw to pick up too much momentum or be caught by a gust of wind. “We can fly up to a wind speed of about 45 km/h (28 mph). In stronger winds, it’s too dangerous,” says Jäger. However, he’s never bungled a cutting job so far, he adds.

Personal meets professional passion

More on vehicle converter Timo Haug

The vehicle converter: Personal meets professional passion

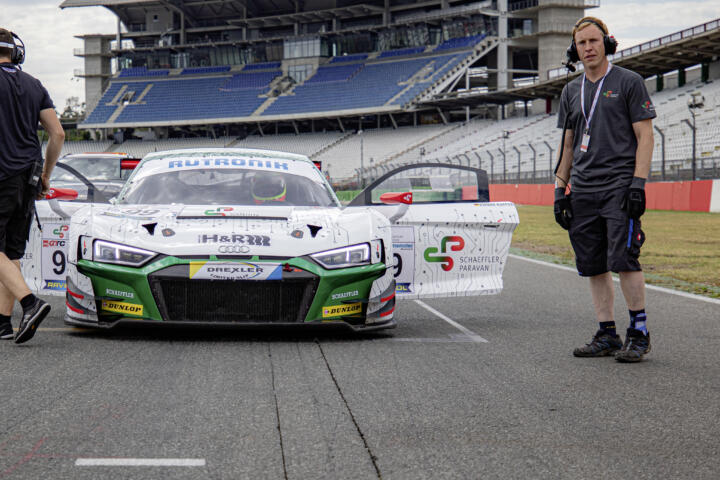

There’s a reason for the broad smile on Timo Haug’s face. His job has taken him to the place to which his private passion attracts him, too: the race track. Haug is an avid kart driver and motorsport fan. His job at Schaeffler Paravan has now resulted in a private and professional overlap. On the job, the 38-year-old equips vehicles for people with disabilities with Schaeffler Paravan’s drive-by- wire technology Space Drive. In addition, Haug develops customized Space Drive solutions for prototypes – from microcars to trucks – for client projects. All in all, a highly varied field of work that in 2018 was extended by a very attractive facet: a race car with Space Drive.

-

© Schaeffler Paravan

-

© Schaeffler Paravan

To demonstrate the capabilities of the technology on the one hand and to gain further development input from using the system at the limit on the other, Schaeffler-Paravan converted an Audi R8 LMS into a steer-by-wire race car. The steering column was removed and a force-feedback steering wheel operating with electrical impulses installed. Timo Haug was involved in the project from day one. The innovative race car was the first of its kind to be approved by the German Motorsport Association (DSMB) and competed in the DMV GTC series. For four races, Timo Haug switched from the production hall in the southern German town of Aichelau to the garages at race tracks like Nürburgring and Hockenheimring. “It’s exciting to keep developing this system under these extreme conditions,” he says. “When the car raced past us at 250 km/h (155 mph) for the first time without a steering column, that was a real goose bump moment.”

Ensuring that the mugs are filled

More on flow specialist Uwe Daebel

The flow specialist: Ensuring that the mugs are filled

The Munich Oktoberfest is the world’s biggest folk festival. 6.3 million people in partying mood flocked to the “Wiesn” in 2019. Most of them just came for one thing: drinking beer. A total of 7.3 million liters (1.93 million gallons) this year. Uwe Daebel, Head of Filling and Packaging Technology at the Paulaner Brewery, is the man who’s instrumental in ensuring that the stream of beer never runs dry. His company is the supplier to 18 large and smaller beer tents at the Oktoberfest. It’s a high-pressure job in more ways than one. Especially in the large tents, where up 9,300 people want to be served, the supply became increasingly difficult. Uwe Daebel rose to the challenge by coming up with the idea of using a ring line to supply each of the three largest tents with beer. Amazingly, “The system operates without mechanical pumps; only carbon dioxide acting as a pressurizer pumps the beer to the taps,” Daebel explains. Sounds simple, but there’s a lot control technology and software from Siemens working in the background. Via an internet connection, Daebel can read all the relevant data on his “Mug-o-Meter” from anywhere in the world: flow speed, consumption, pressures, temperatures, fill levels, and so on.

-

© Siemens

-

© Siemens

In addition to all the beer, carnival rides at the Oktoberfest may cause visitors to feel like they’re spinning. Contactless radar technology measures the fill level of the beer kegs

First thing in the morning, Daebel looks at his “Mug-o-Meter” to check if the scheduled amount for the day was actually delivered overnight or, as Daemel puts it, if the tanks have been unloaded, and the status of the system. Daebel: “If fest tent mode is activated I know that the tank unloading at night was successful. Otherwise I try to get in touch with the tank crew and discuss the relevance of the trouble with them.” If all else fails, the 62-year- old himself will check and troubleshoot before the beer tent opens, or else there’ll be long faces among the visitors – and the tent operators. Every hour of system failure would amount to 12,000 unsold mugs equating to lost sales of about 130,000 euros.