Inner drive

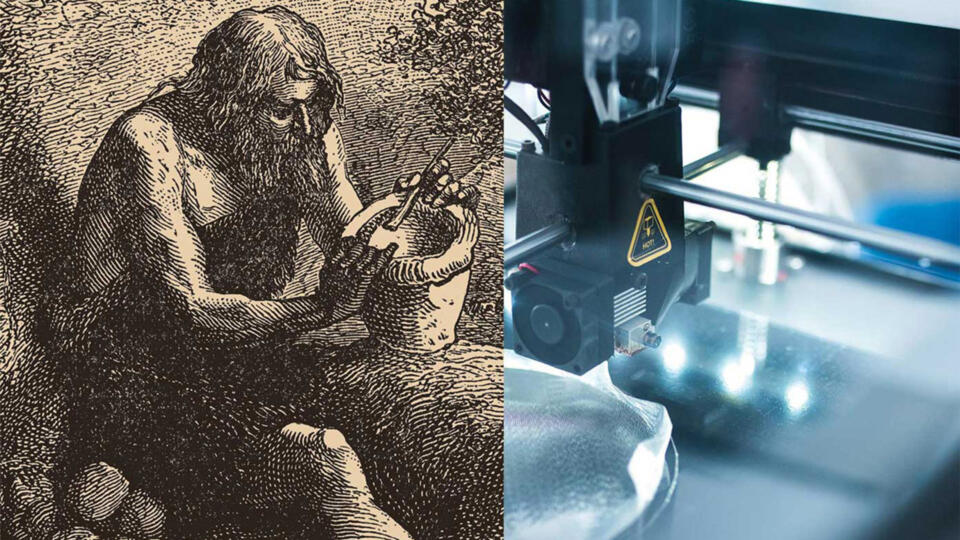

Our planet is not a place flowing with milk and honey. Humans have been going to work since time immemorial, if for no other reason than to satisfy their need for food – and have been doing so to this day. The first pre-historic jobs were those of hunters and gatherers. These activities serving the pure purpose of getting hold of food are commonly deemed to be humanity’s oldest traditional economic system. Hunters, by the way, were also the first humans to use tools. The oldest hunting weapon found so far, a spear, is 300,000 years old.

The body’s own reward

The realization that work not only satisfies our need for subsistence but can also make us happy is hundreds of thousands of years old, too, and can be explained by the fact that even the evolutionary ancestors of humans used to live in social groups. Only those who were socially accepted and belonged to a group were able to survive. Therefore, in the course of evolution, the human brain developed sensors enabling us to perceive the quality of social relationships, plus a network of nerve cells residing in the midbrain that’s referred to as our motivation and reward system. When a human being – back than or today – experiences social recognition and appreciation the system releases a cocktail of happiness composed of ingredients like dopamine (an energy drug ), oxytocin (a confidence and collaboration messenger substance) and internal opioids (messenger substances that make us feel good): a reward paid out by our brain.

Not what I have, but what I do is my kingdom

Thomas Carlyle,

Scottish historian

These findings have led to important conclusions for today’s working world, says the neurobiologist, physician and book author Prof. Dr. med. Joachim Bauer (“Arbeit – warum sie uns glücklich oder krank macht” – “Work – Why It Makes Us Happy Or Ill”): “People can only sustainably muster up commitment and motivation if they experience that what they do is perceived, acknowledged and appreciated. This doesn’t mean at all that employees want to or should be pampered and constantly showered with praise. Even criticism can be perceived as a form of appreciation – provided it’s justified and not communicated in disparaging ways. By the way, the necessity of ‘being seen’ not only applies to the job but also to activities in people’s private lives.”

Naturally, these mechanisms can also be undermined. The ancient Greeks and Romans for example did not value physical labor in any way. They only managed to evolve into advanced civilizations because slaves took care of all physically strenuous activities and thereby kept things running. Work and social life in Rome and Athens were by and large separate entities.

Upward mobility through work

This development only began to change in the Middle Ages. While the underprivileged and unfree rural population – which accounted for 90 percent of the total population in Europe at the time – perceived its unappreciated labor as a hardship and daily grind, craftsmen in the cities developed a rather self-confident attitude about their work. “Work ennobles” became the slogan for upward mobility. Technical progress additionally spurred the growth of crafts. In larger medieval cities, there were as many as 100 different types of them. As blacksmiths, tailors or cobblers weren’t able to eat the fruits of their labor and barter exchange became increasingly complicated the practice of paying money for work that has been preserved to this day became more and more prevalent. Naturally, the amount of money was also an expression of how much the work for which it was paid was valued and thus provided an additional stimulant to the reward system in the midbrain.

The example of the Fuggers, a family of former weavers, proves the truth of the old adage: A trade in hand finds gold in every land. From early 16th century Augsburg, Jakob Fugger ruled over a global merchant and banking empire “in which the sun never sets” as the saying went in those days. Expressed in today’s terms, his assets purportedly amounted to 400 billion dollars, which would make him the richest person in history, even surpassing all the Bezos, Gates and Buffets of today’s world. “Work ennobles” and the Fuggers were an extreme example of the veracity of this phrase. Other families of craftsmen managed to rise to the level of the middle class as well, and in doing so defined the importance and worth of work that’s still valid today. Reformer Martin Luther spurred the diligent on by pithy statements: “Humans are born to work like birds are born to fly,” he found, and even criticized the upper class’s common indulgence in sweet idleness as a form of blasphemy: “Idleness is a sin against God’s commandment, who has commanded us to work here.”

The meaning of work

But let’s return to the crafts once more, which to this day are deemed to be particularly fulfilling, as repeatedly confirmed by surveys. Creating something with one’s own hands: from A to Z, something of lasting value. All this releases a rush of happiness cocktails from our reward center.

However, in the middle of the 18th century, the happy hour in the brain begins to get lost in the wake of the industrialization of work. A unique piece of work turns into a product, mass-manufactured with the help of machines. At the beginning of the 20th century, the assembly line starts splitting production into monotonous work steps. The previous satisfaction factor derived from the feeling of having created something now practically equals zero. However, there are two other reasons why industrialization dehumanizes work: one is that low-cost machine manufacturing cuts the ground from under the feet of many craftsmen and the other, even more important one is the precarious working conditions in the factories, especially in the early days of industrialization. Many people at that time moved from the country to the cities. In London alone, the population between 1800 and 1900 grew from one to nearly seven million. Rural people were almost magically attracted by the hope that their labor would be appreciated more in the new factories than on the estates of landlords. However, the sudden excess supply of labor caused the workers to become serfs of the factory owners.

Horrible working conditions, lousy pay and degrading living conditions soon drove people to go to the barricades: no wonder when a six-day 96-hour work week is not enough to feed a family. “The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win,” said Karl Marx’ in a rallying cry that was heard by the masses. All over the world, there were uprisings by labor movements as the proletariat was revolting against the moneyed and landed aristocracies.

43 different smithing specializations

have been identified in historic records about medieval Cologne. For instance, there were blacksmiths, farriers, and smiths that would forge nails, scissors, helmets, axes, boilers and pans. Bell-makers and pewterers, needle-, spur- and spear-makers were related crafts. Unsurprisingly, the last name Smith, derived from this metal-working occupation and said to have originated in England, and its various forms in other languages is ranked in eighth place of the most common last names worldwide.

Ein neuer Sektor entkoppelt sich

Many things subsequently improved in the factories. However, increasing automation cost many of the jobs that had just been created – albeit they were more than offset by new ones. Today, in our post-industrial age of a service economy, 70 percent of all people in the countries now falsely labeled as industrial nations are working in the tertiary sector. At the moment, a fourth one, the information sector, is beginning to split off from the world of services.

Developments that changed the world of work

The prehistoric human hunter has evolved into a data gatherer and now we’re no longer weaving fabrics but algorithms. Yet when you ask young people what drives and motivates them the answer is still the same as that of their forebears: social recognition and appreciation. Just like way back when we’d gather around a fire in front of a cave. Let’s drink to that with a happiness cocktail.