Challengers of partiarchy

The physician

Agnodike (~300 BC)

If we can believe Gaius Julius Hyginus, Agnodice was the first female physician in antiquity. According to his accounts, she lived in ancient Athens around 300 BC and studied medicine and midwifery under Herophilos. Since women are not allowed to study or practice medicine, Agnodice cuts her hair short and wears men’s clothes – which of course raises the question of how her teacher could have missed the fact that his student was a woman. Following her training, Agnodice goes on to practice gynecology so successfully that envious colleagues accuse her of seducing her patients. To exonerate herself, she reveals her true gender – and faces another trial. Only when courageous Athenian women of influence intervene – purportedly, they even threatened to leave their husbands – Agnodice is acquitted. And not only that: the law is changed, henceforth allowing women to study midwifery and medicine, and to treat female patients.

About women who pretended to be men

Agnodice was neither the first nor the last woman to pretend she was a man. Two further examples: At the beginning of the 19th century, the French mathematician Sophie Germain sends her work on number theory to Carl Friedrich Gauss under a male pseudonym. At the beginning of the 20th century, the German chemist Ida Noddack disguises herself as a man in order to attend lectures to which only men are admitted.

The polymath

Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179)

It would be unfair to reduce Hildegard von Bingen’s achievements to those of an esoteric healer. Although the abbess also has a wealth of knowledge about herbs she is, first and foremost, a scientist and composer, and one of the most amazing persons of the High Middle Ages. Born in 1098 as the last of ten children, she is put into the care of a convent due to her frail health. Even as a child the subsequent polymath has “religious visions.” Today it is assumed that she was suffering from migraine headaches. Hildegard von Bingen not only masters the challenge of founding two convents but goes on to become an adviser to influential personages of her time, monarchs such as Frederick Barbarossa or high-ranking members of the clergy up to and including the pope: amazing mojo for a woman who lived at a time when contemporary writings would describe women as “inferior” and therefore “having to subordinate themselves to men.”

About women in the Middle Ages

The story was a worldwide success as a book and a movie – but did Pope Joan really live? Several medieval sources mention a woman who purports herself to be a man and rises to the highest ecclesiastical office. However, fiction and truth are often not far apart from each other in papers written in those days. It’s also possible that “Pope Joan” was Marozia. From 914 on, the Roman senatrix bends several popes to her will and in doing so establishes a rule of mistresses (“pornocracy”). Pope Joan is said to have lived at about the same time.

The computer scientist

Ada Lovelace (1815–1852)

In 1843, she writes the first computer program – and, essentially, it’s her dissolute father’s fault. Ada Lovelace is the daughter of the poet Lord Byron. Her parents separate one month after her birth. To prevent Ada from following in her father’s footsteps, her mother bans any kind of poetic note from Ada’s education and instead has her taught in natural sciences – by the famous mathematician Augustus De Morgan, among others. De Morgan recognizes her talent but doesn’t promote it because he basically deems women to be unsuitable for science. The young girl only feels all the more challenged by his attitude: At the age of twelve, Ada designs a flying machine modeled on a dead crow, with a steam engine to power the wings. Unfortunately, the machine won’t fly. At the age of 17, Ada meets Cambridge professor and mathematician Charles Babbage. His project: the Analytical Engine, a mechanical computer that is decades ahead of its time, albeit will never be built. Ada Lovelace recognizes its potential, more than its inventor does. She writes a numerical list of commands with operations and variables – which today is acknowledged as the first computer program. One sentence in her papers is currently being hotly debated in the wake of the advance of artificial intelligence: “The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform.”

About female IT pioneers

Grace Hopper (1906–1992) in the late 1940s comes up with the idea of writing computer programs in an understandable language instead of just in ones and zeros. In pursuing her idea, Hopper performs important preliminary work leading to the development of the COBOL programming language. Hopper (her motto: “If in doubt – do it”) receives more than 90 awards in recognition of her achievements. Curiously enough, in 1969, the Data Processing Management Association presents her with its “Man of the Year” award. Which goes to show how rare women like “Amazing Grace” – as many of her admirers call her – are in the IT sector in her day.

The aviator

Élise Deroche (1886–1919)

“The Aéro-Club de France, Paris, certifies that Madame de Laroche has been licensed as an airplane pilot. March 8, 1910. The President.” The history of motorized aviation is still young in those days. Only seven years earlier, Orville and Wilbur Wright succeeded in performing the first seconds-long flights. Madame de Laroche is born Élise Deroche around 1885 to a family living in modest circumstances. She later tries her luck as an actress, calls herself Baroness Raymonde de Laroche, and meets aircraft constructor Charles Voisin, who suggests that she learn to fly. The courageous young woman welcomes the challenge. At the first opportunity that presents itself, she takes off in his single-seater without permission. The year is 1909. Her flight instructor is less than enthusiastic, but be that as it may, her flight marks the first ever solo of a woman in the history of aviation. Deroche feels that flying is the best possible thing for women: “Flying does not rely so much on strength, as on physical and mental coordination.” Right after receiving her pilot’s license, Mme Deroche crashes in Reims and is rescued with severe injuries, but just two years later, the Frenchwoman is flying again. “Perhaps I’ll tempt fate once too often. But I have dedicated my life to aviation and always fly without a trace of fear,” she says. On July 18, 1919, she dies in a crash landing after a test flight with an experimental plane.

About female aviators

In 1935, the American Amelia Earhart is the first person to fly solo across the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and California. Two years later, she embarks on the first equatorial flight around the globe. Earhart has completed three quarters of the distance when she disappears somewhere in the South Sea. In a comment preceding this flight, she reportedly said: “Women, like men, should try to do the impossible. And when they fail, their failure should be a challenge to others.”

The scientist

Marie Curie (1867–1934)

One should assume that a remarkable female scientist inspires nothing but admiration – yet even during Marie Curie’s lifetime the press writes that she is a “strange woman.” But let’s start from the beginning: Marie Curie is born Maria Salomea Skłodowska in Warsaw in 1867. Women are not admitted to universities there, so in 1891 she moves to Paris to study at the Sorbonne. Even there the gender ratio shows the great challenge that a university education poses to women in those days: only 23 of more than 1,800 students are women. The educational migrant – besides finding her future husband, the physicist Pierre Curie – discovers polonium and radium. Later, she’ll be the first woman to teach at the university, albeit only after her husband has died in a road accident and the chair in the physics department he previously held is bestowed on her. Three years earlier, she had been the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in physics together with her husband Pierre Curie and her doctoral thesis supervisor, Henri Becquerel. In 1911, she receives the most distinguished scientific recognition once more, this time in chemistry and without having to share it. Curie’s daughter Irène, by the way, will subsequently follow in her footsteps and in 1935 receive the Nobel Prize in Chemistry as well. Her mother is no longer alive at that time: on July 4, 1934, Marie Curie, aged 67, dies of the consequences of decades-long handling of radioactive materials. Albert Einstein says about her: “Marie Curie is, of all celebrated beings, the only one whom fame has not corrupted.”

About recognition

That Marie Curie in 1903 is awarded the Nobel Prize on an equal footing with her husband and her fellow scientist Becquerel was not to be taken for granted. Even decades later women, who were instrumental in achieving breakthroughs in scientific research projects, are ignored, like Jocelyn Burnell. In 1967, aged only 24, she discovers the first radio pulsar, but the Nobel Prize goes to her thesis supervisor Anthony Hewish. Rosalind Franklin is another example. The English scientist in the 1950s is decisively involved in the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA. The Nobel Prize for this discovery, though, is awarded to Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins, who had availed themselves of the results of her research without her knowledge.

The motorists

Effie Hotchkiss (1894–1966)

Adeline Van Buren (1894–1949)

Augusta Van Buren (1894–1949)

Clärenore Stinnes (1901–1990)

The first-ever cross-country motorized drive in human history was undertaken by a woman (see box below). Even so, women at the wheel of motor vehicles were a rare sight for many years, particularly if the trips were adventurous. Effie Hotchkiss, merely 20 years old, and her mother, Avis, take on such a challenge in early 1915. In a Harley-Davidson motorcycle-side car combination, they rumble across the United States from New York to San Francisco, covering a 9,000-mile (14,000-kilometer) distance, mostly on dusty or even muddy unpaved roads that were typical in those days. Not least due to these hardships, the “Orange County Times-Press” on April 23, 1915, wrote about the two adventuresses that they were an interesting example of how far women could go with determination. A year later, the Van Buren sisters, Augusta and Adeline, tackle the challenge of crossing the United States. The reason for their journey: “Gussie” and “Addie” want to serve in the military – as dispatch riders. Their applications, however, are rejected. Not acceptable, the sisters find, and intend to prove how well-suited they are for the job. “Woman can, if she will,” is Augusta’s motto. On July 4, 1916, Independence Day, they embark on their journey on two heavy Indian Powerplus (998 cc, 18 hp) motorcycles. In spite of being arrested on numerous occasions for wearing men’s clothes, they master their awesome ride – albeit they won’t get the coveted job as military dispatch riders after all. In the 1920s, Clärenore Stinnes dares an even greater adventure of surrounding the whole world in an automobile. As on previous occasions, her family raises eyebrows about the avid race driver’s boyish zest for action: around the world in a car, are you serious?! You bet she is! Not least thanks to benevolent support by the automotive industry. Frankfurt-based Adler-Werke provide their latest “Standard 6” production sedan: 6 cylinders, 45 hp, 80 km/h (50 mph) top speed. On May 25, 1927, the 26-year-old departs from Frankfurt, accompanied by two mechanics, Swedish cameraman Carl Axel Söderström (whom she will later marry), plus a travel budget of 100,000 reichsmark. The eastbound trip becomes increasingly strenuous. Söderström: “I pushed the car more than I shot footage.” Heat in the Syrian desert, ice at Lake Baikal, mud in Siberia, rough terrain in the Andes – none of this stops Clärenore Stinnes. After having driven a distance of nearly 47,000 kilometers (30,000 miles), she and her team arrive in Berlin on June 24, 1929, greeted by a cheering crowd.

About female motorists

In August 1888, Berta Benz – without her husband’s knowledge (“Carl would have never allowed it”) – drove the Benz Patent Motor Car Number 3 from Mannheim to Pforzheim (106 km/66 mi) in Germany. The trip not only made her the first woman to operate an automobile but also the first person to go on a cross-country automobile journey.

The telecommunicator

Hedy Lamarr (1914–2000)

In 1843, she writes the first computer program – and, essentially, it’s her dissolute father’s fault. Ada Lovelace is the daughter of the poet Lord Byron. Her parents separate one month after her birth. To prevent Ada from following in her father’s footsteps, her mother bans any kind of poetic note from Ada’s education and instead has her taught in natural sciences – by the famous mathematician Augustus De Morgan, among others. De Morgan recognizes her talent but doesn’t promote it because he basically deems women to be unsuitable for science. The young girl only feels all the more challenged by his attitude: At the age of twelve, Ada designs a flying machine modeled on a dead crow, with a steam engine to power the wings. Unfortunately, the machine won’t fly. At the age of 17, Ada meets Cambridge professor and mathematician Charles Babbage. His project: the Analytical Engine, a mechanical computer that is decades ahead of its time, albeit will never be built. Ada Lovelace recognizes its potential, more than its inventor does. She writes a numerical list of commands with operations and variables – which today is acknowledged as the first computer program. One sentence in her papers is currently being hotly debated in the wake of the advance of artificial intelligence: “The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform.”

About Hollywood

1970, 1980, 1990 … guess what year a woman won the Academy Award for Best Director for the first time? It’s hard to believe but it’s not until 2010 that Kathryn Bigelow is the first and so far only woman to win this distinction for her work on “The Hurt Locker” in the 91-year history of the Academy Awards.

The chemist

Stephanie Kwolek (1923–2014)

That she had a special interest in fashion is somewhat surprising. But this is exactly what the chemist Stephanie Kwolek, who developed Kevlar in 1965 and as a child was incessantly sewing clothes for her dolls, said. The American of Polish descent would have liked to have become a physician. To raise money for medical school, she takes a temporary job at chemical corporation DuPont. The work there suits her so well that she decides not to pursue a medical career. In 1964, she discovers liquid, crystalline polymers that can be processed into synthetic fibers. The material, subsequently better known as Kevlar, is five times harder than steel yet amazingly lightweight. The synthetic fiber is still used in bullet-proof vests, helmets and aircraft today. The scientist herself will later refer to her discovery as a “lucky coincidence” in the “Washington Post.” This can be assumed to be an understatement, especially since she has to persuade her colleagues to spin the material like a fiber. She does not, by the way, directly benefit from the profits DuPont generates with Kevlar. In 2014, she dies at the age of 90. A few years earlier Kwolek says in an interview: “At least I hope I’m saving lives. There are very few people in their careers that have the opportunity to do something to benefit mankind.”

About female inventors

Born in 1867, married at 14, a mother at 18, widowed at 20 – Sarah Breedlove has to “woman up” early in life. When she suffers hair loss at age 33, she experiments with an antidote and later goes on to develop a gel to straighten curly hair with a “hot comb” – a huge success with African-American women that lays the foundation for a cosmetic empire. Its name is Madam C. J. Walker, a name Sarah adopts after marrying her second husband. She becomes the first female self-made millionaire. Walker not only uses her wealth to have a mansion built in New York next to the Rockefellers, but gives generously to charity and supports the fight for equal rights of African-Americans. It is a short life as an entrepreneur, activist and philanthropist: Walker dies, aged only 51.

The sailor

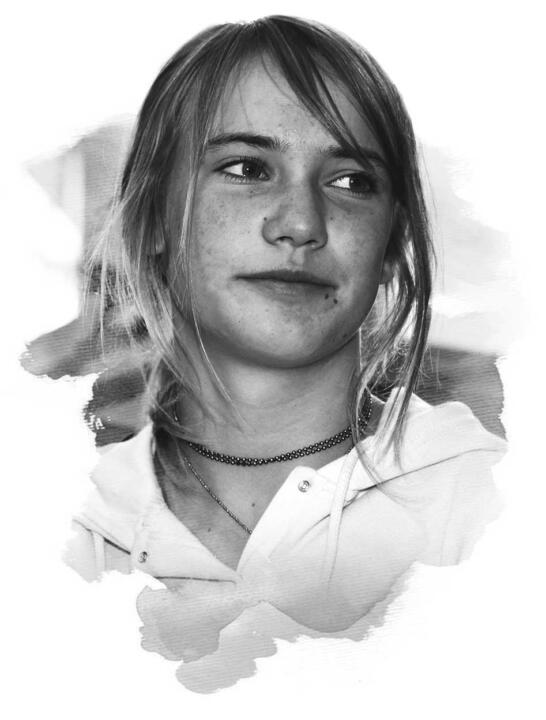

Laura Dekker (*1995)

She doesn’t want to go to school and definitely not live in a house. Laura Dekker, born in New Zealand in 1995 to Dutch-German parents, is strong-willed and determined to tackle a very special challenge: sailing around the world in her two-masted ketch “Guppy” at age 14. In 2010, she sets sail after a court has previously ruled against her journey. Child welfare authorities had intervened, plus her plan is hotly debated in pubs, sailing clubs and the media. Is it okay to let a child sail around the world? Laura prevails – with support from her family. The 50,000-kilometer (31,000-mile) trip starts in Gibraltar and, on January 21, 2012, ends on the coast of the Dutch Caribbean island of St. Maarten. At age 16, she secures the “behind-the-scenes” title of “youngest solo circumnavigator.”The accolade will never become any more official than that due to fears that others might want to follow her example. Today, Laura Dekker is 23 years old and planning to build a boat: “Guppy XL,” an ocean-going two-masted ketch, 24 meters (79 feet) long. She intends to start sailing it in 2022, albeit not alone. “I’d like to show children and teenagers how to cut their own path and make their dreams come true,” she says.

About female circumnavigators

A woman who played an important part in paving the way for Laura Dekker is the British sailor Tracy Edwards. 30 years before Laura’s journey, Edwards contested the tough Whitbread Round the World Race with her yacht “Maiden” and an all-female crew – an affront against the ocean regatta world that was dominated by men up until that time. The female skipper receives threatening letters, her front yard is polluted by oil, and the sailing press accuses her in advance of being at fault in the event of an accident. But the “Maiden” finishes as the second-fastest boat in class – and changes female sailing for good.